Theme

China’s approach to WTO reform does not address the key problem which has been instrumental in the increasingly poor working of the WTO, namely the presence of a very large non- market economy within its constituency.

Summary

It is hard to think of a more important event that might have shaped the future of the WTO than China’s accession in December 2001. In the same vein, WTO accession is clearly one of the most consequential changes to China’s economic model on which Deng Xiaoping’s ‘reform and opening-up’ campaign leveraged the most.

China offers a paradigm of an emerging –but also a planned– economy opening up to the world. In fact, a number of countries that were either part of the Soviet Union or in its sphere gained WTO accession before China. More specifically, five former members of the Soviet Union, namely Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Estonia, Georgia and Lithuania, together with others in the Soviet Union’s sphere, such as Albania and Bulgaria, succeeded in becoming WTO members between 1997 and 2001. China’s accession, though, was very different as it started well before and was much lengthier and tempestuous. Interestingly, however, China also experienced a much faster transformation than any of these countries, at least in terms of economic growth. This analysis explores the reasons behind China’s transformation, what it means for the WTO and the ongoing discussion on China’s approach to WTO reform.

Analysis

China’s accession to the WTO and its economic success

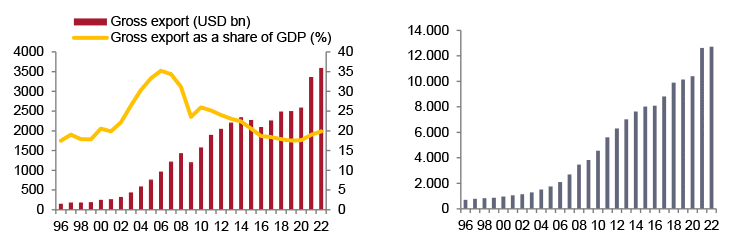

China’s economic success in the past few decades is clearly linked to its accession to the WTO but not only in terms of market entrance. In fact, China’s accession to the WTO brought about reforms since they were tied to fulfilling China’s entry commitments. The success is undeniable: within five years, the share of exports in its GDP rose by 10 percentage points, from 18% in 2001 to almost 29% in 2005 (see Figure 1). Thanks to the export-led growth model, China’s rapid export growth has been accompanied by rapid growth in income. GDP per capita more than doubled from US$1,053 to US$2,099 from 2001 to 2006 and multiplied almost 10-fold to US$10,261 in 2019, before the COVID pandemic struck the Chinese economy and the world (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Chinese exports, 1996-2022. Figure 2. China: per capita GDP, 1996-2022 (US$)

Source: UNCTAD. Source: The World Bank.

China’s accession to the WTO was preceded by a lengthy process of negotiations that required significant reforms to transform its economy into a more market-based model. The results of bilateral negotiations on market access were extended to all members under the most-favoured-nation principle. Regarding market access for goods, China agreed to reduce import tariffs and to eliminate quantitative restrictions on imports by 2005. China also committed to unifying all laws, regulations and standards, applying discriminatory standards to imports by the time of its accession to the WTO, and to ensure the transparency of the system as well as the equal treatment of imports and domestic products.

China’s concessions on market access for services was more limited but it did agree to a phase-out of restrictions to the entry of foreign investors, which vary widely across sectors. It is also important to look into the safeguard, or emergency measures, allowed by the WTO (Shaffer & Gao, 2018)[1]. These measures ordinarily take the form of tariff hikes or quantitative restrictions. Subsidies are an exception to the principle of national treatment and the WTO agreement does allow subsidies to be provided to domestic industries only. Government procurement is also an exception to the principle of national treatment. Governments are allowed to preferentially purchase domestic goods when sourcing goods as the final consumer. The WTO agreement sets forth rules on these measures so that they are not abused to create barriers to trade. As a general principle, China was required to adhere to these rules when joining the WTO, but conditions differ according to the specific agreement.

The very important issue of adherence to commitments to subsidies has so far been watered down as China has kept is status as a developing economy until today. Regarding procurement, China decided not to join the plurilateral agreement binding members to international procurement rules and the situation has not changed. At any event, as part of the accession process, China has agreed to guarantee non-discrimination against foreign and foreign-capital companies in applying conditions to the procurement of inputs and goods and services. It is also committed to eliminating the discriminatory two-tiered pricing system for foreign companies purchasing transport, energy and telecommunications service charges. In terms of protecting intellectual property, China amended legislation to bring it in line with obligations of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Among several actions, China amended its criminal law, adding penalties for intellectual property rights infringement, provided a legal framework for protecting intellectual property rights by the customs authorities, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) was given power to prosecute infringements, and a specific section was set up at the Supreme People’s Court to handle this. Still, infringement is rampant. In the case of technology transfers, the legislation in China remains valid, in contradiction to the TRIPS agreement, such as the ‘Technology Importation Contract Control Ordinance’ and concomitant enforcement rules, which impose restrictions on international technology importation contracts (ie, licensing contracts).

As for standards and certification, the WTO, under the GATT non-discrimination principles, contains rules on technical standards and certification so that arbitrary standards and technical requirements at the national level do not constitute technical barriers to trade. China was very far from the WTO’s commitments on this front at the time of accession. Different authorities or institutions were in charge of product inspections depending on whether the product was domestic or imported. Also, the standards by which products were inspected lacked transparency. Various steps have been taken since, including the creation of China’s compulsory certification, but problems leading to discrimination towards foreign products remain.

Finally, for anti-dumping and countervailing duties, China formulated its own legislation in 1997 and began investigations at the end of that year into newsprint from Canada, Japan, the Republic of Korea and the US but its legislation was not in line with that of the WTO. Regarding the use of anti-dumping and countervailing duties against China by WTO members, it is important to note that the scope and approach change substantially depending on whether China is considered a market economy. The US-China bilateral agreement for accession in November 1999 treats China as a ‘non-market economy’ for the first 15 years after accession and allows the use of third-country domestic prices and production costs in the calculation of normal values.

China as a key factor behind the need for WTO reform

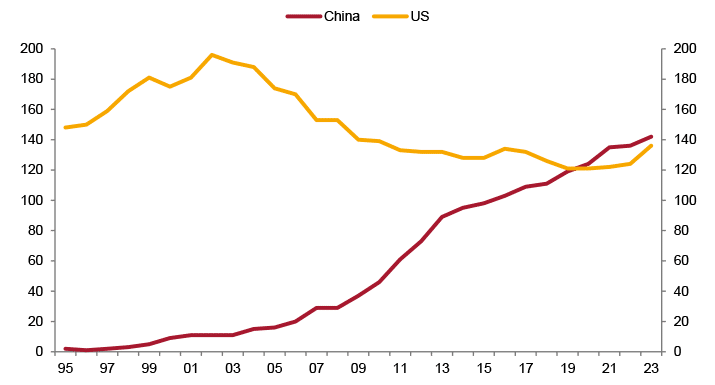

While China was not the first or even the last non-market economy to enter the WTO (Vietnam followed China, for example), there are a number of reasons why China is a much more important case for the future of the WTO and the need for reform. The most obvious reason is China’s sheer size. China today is the second-largest economy in the world, or even the first when measured in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). In addition, its companies have continued to grow, and now top the rankings of the world’s largest companies. In fact, China now has more Fortune 500 companies than the US (see Figure 3), which means that any distortions in an economy the size of China’s, which also has such a large number of huge companies, have global implications. Vietnam cannot really compare with China, in either size or influence. The other important reason why China makes a case for WTO reform is related to the substantial role played by the state in the Chinese economy.

Figure 3. China and the US: number of companies in the Fortune 500, 1995-2023

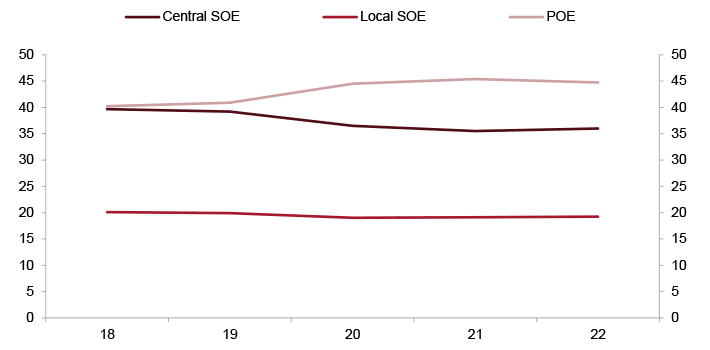

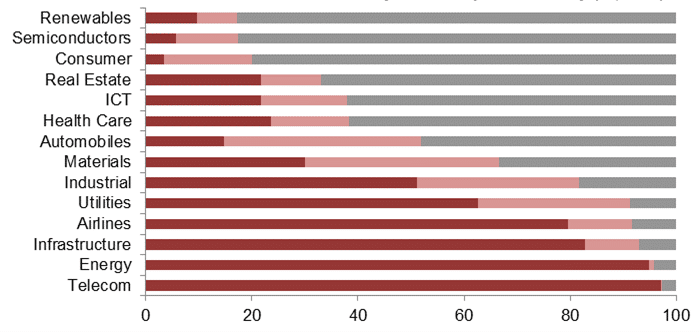

The role of the state in the Chinese economy has long been debated both in the economic literature and in political circles, and the dispute has by no means been settled. To this end, we look at the share of corporate assets still in state hands, particularly among listed companies. In fact, as of the first half of 2022, 55% of assets were in the hands of SOEs, regardless of whether they were central or local SOEs. This percentage is even higher in the telecom, infrastructure, airline, energy and utility sectors (see Figures 4 and 5). While the pervasiveness of state control in the production of goods and services already points to potential distortions in the Chinese economy, pushing it away from market functioning, one could argue that ownership does not necessarily determine how a company might behave. In fact, the concept of ‘competitive neutrality’ is designed to measure how close the behaviour of a state-dominated entity may be to that of a private company in the production of goods and services. In a paper by García-Herrero & Ng (2021)[2], the authors measure sector by sector how far Chinese SOEs are from competitive neutrality in the domestic market. They find that SOEs are generally advantaged compared to their private counterparts except for the real-estate sector.

Figure 4. Chinese firms: total assets by ownership, 2018-22 (%)

Figure 5. Chinese firms: total assets by ownership and industry, 2022 (%)

Another important role of the state in the economy is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is intrinsically involved in the functioning of companies in China. In particular, the CCP appoints and controls key company executives through the CCP Organisation Department. In addition, both state-owned enterprises and private Chinese companies have internal Party committees that are capable of performing government and Party functions. In recent years, moreover, the Party has taken steps to increase the strength and presence of Party committees within all companies. For example, state-owned enterprises and private Chinese companies are being pressured to amend their articles of association to ensure Party representation on their boards of directors, usually as the Chairman of the Board, and to ensure that important company decisions are made in consultation with Party cells. Further reinforcing the Party’s influence over enterprises in China is the Social Credit System, which monitors and rates individuals and companies in China, including foreign ones. More generally, the strategic planning stemming from China’s latest Five-Year Plans and beyond makes it very clear that China wants to remain a socialist economy with Chinese characteristics and that the overarching role of the state is not going to wane. Both China’s growth and economic model have a huge impact on the function of the WTO, making a reform even more necessary, in addition to other reasons.

China is obviously not the only country with a state-led economic model, which means that a reform is bound to affect many other economies. The most serious issue is related to the SOEs that dominate many economies, especially in the Gulf countries and Vietnam. There are basically no specific obligations regarding SOEs within the WTO agreement. The Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) does not even mention SOEs. The second key issue is technology transfer. The US and others have also voiced concerns about China’s use of informal nonstate channels and informal norms not openly articulated by a government official. The issue is only partly addressed within the existing WTO rulebook, which fails to specify what constitutes a ‘forced’ technology transfer. The GATT and other multilateral agreements do not cover investment for goods, nor do they therefore address transfers of technology. On the other hand, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) is the only multilateral agreement that covers investment. In addition, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs Agreement) has something to say about this as well.

The other important issue is the developing country status. The WTO treaties provide certain exceptions and more permissive rules for developing countries, which, under the special and differential treatment (S&D), are entitled to longer time periods for implementing agreed commitments, measures to increase trading opportunities and twice the number of agricultural subsidies available to developed countries. However, there are no set rules for what constitutes a ‘developing country’ –meaning that this is an issue of self-declaration–. Most of the WTO’s members claim to be developing, including China. Hence, the system allows China to enjoy preferential rules in some areas, despite the fact that it is a larger trading power than many advanced economies, that it has the largest number of Fortune 500 companies and that it is the first-/second-largest economy in the world. It seems clear that WTO rules were not crafted with the unique structure of China’s political economy in mind and that reform is clearly needed.

China’s proposal for WTO reform and how the EU proposal relates to China

China has submitted two formal documents on the topic of WTO reform: the Position Paper on WTO Reform of November 2018; and the Proposal on WTO Reform of May 2019 (WTO, 2019). In general, China’s primary focus is how to bring the Appellate Body to work again but also, fisheries subsidies, e-commerce and investment facilitation. As for the more controversial topics such as trade distortions and subsidies, China still defends its interests and stresses the uniqueness of its economic structure. Key complaints such as forced technology transfer are not mentioned in the proposals even though China did respond by introducing a new investment law in 2019 that prohibits forced technology transfers. Regarding the behaviour of SOEs, China maintained a tough position and reasoned that SOEs are equal players in the market whose only difference is ownership. In that regard, China would like to avoid discrimination against SOEs in foreign investment security reviews by WTO members. In other words, China’s position is that it would accept discriminatory discipline on SOEs in the name of WTO reform and that foreign investment security reviews should be conducted in an impartial manner.

As for subsidies, China does admit the potential misuse and abusive application of trade remedies, in particular discriminatory practices based on country-of-origin and types of enterprises. However, it attributes the problem to the ambiguities in existing multilateral trade remedy rules. As such, it proposes to further clarify and improve relevant WTO rules on subsidies, countervailing measures and anti-dumping measures. That said, it still stresses the need to give consideration to the special situation of developing members and gives no sign that it will move away from a such status.

The aspects of the EU proposal which refer directly to China show how far the two positions are on key topics regarding global competition. First, according to the EU, market distortions from non-market economies should be one of the key objectives to be addressed in the WTO reform. As regards subsidies, the EU expects to improve transparency beyond the existing agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) since the lack of information makes it close to impossible to pursue cases at the WTO. Regarding SOEs, there is the additional problem that they are currently classified as ‘public bodies’ and thus escape the responsibilities imposed by the SCM Agreement. For the EU, WTO reform would need to clarify the commercial nature of SOEs so that they are fully covered by existing WTO commitments on subsidies and other non-market practices.

Finally, the EU proposal does recognise that, even with better transparency on subsidies and better coverage of SOEs in existing mechanisms such as the SCM, other-market distorting measures from non-market economies need to be addressed with a WTO reform. To start with, some types of subsidies are still permissible within the SCM, which means that the list of prohibited subsidies would clearly need to be expanded. These include unlimited guarantees and subsidies given to an insolvent or ailing enterprise with no credible restructuring plan or dual pricing. Beyond subsidies and SOEs, the EU proposal also includes new rules to address barriers to services and investment, including forced technology transfers, market access barriers and the discriminatory treatment of foreign investors. Starting with forced technology transfers, the scope of application of existing provisions in the WTO rule is limited and therefore insufficient to address some of the most important sources of problems, such as requirements prohibiting or limiting foreign ownership (eg, joint venture requirements or foreign equity limitations). The final point that the EU position on WTO reform focuses on is the developing versus developed status when it comes to WTO policies (European Commission, 2021). The EU holds the view that the lack of nuance and its consequences with regard to the special and differential treatment question has been a major source of tensions in the WTO and an obstacle to the progress of negotiations. The demand for blanket flexibilities for two-thirds of the WTO membership dilutes the call from a much more targeted group of countries that do have development assistance needs. The EU proposal does not offer a specific solution to this problem, but the direction is clear: reduce the number of countries considered developing and, implicitly, move away from each WTO member deciding on its own status independently.

Conclusions

China’s accession to the WTO has been a landmark event both for China and the rest of the world. In fact, it has been instrumental in embarking an economy of the size of China’s, and bearing in mind the country’s population, in competing in the global economy and the result has been a great success. To achieve that goal, China has no doubt reformed and opened up its economy but not to the extent of becoming a full market economy. That duality –striving to operate as a market economy in some areas while keeping the key characteristics of a state-led planned economy in others– makes it very difficult for China to comply with the principles of what the WTO, as an institution, was designed for. Therefore, a reform is not only necessary but also long overdue. The key problem, though, is that China –and probably other emerging economies with a largely state-led economy or with big industrial policy plans– may feel more comfortable with the kind of WTO rules we have today than with the proposals for reform.

China’s approach to WTO reform does not address the key problem that has been instrumental in the increasingly poor working of the WTO, namely the presence of a very large non-market economy within its constituency. China’s primary focus is how to bring the Appellate Body to work again but it does not deal with the more controversial topics such as trade distortions and subsidies. In fact, in its proposal for reform, China still defends its interests and stresses the uniqueness of its economic structure. Key complaints such as forced technology transfers are not mentioned in the proposals. Regarding the behaviour of SOEs and subsidies, China maintains a tough position and seems to want to retain its favourable treatment as a developing economy.

All in all, under the current circumstances, it seems that WTO reform, as envisaged by the EU, is highly unlikely. In particular, the urgent need to deal with market distortions stemming from China’s economic model and its increasing size and influence in the rest of the world might need to be addressed through other solutions. Multi-country arrangements might be the preferred option while a slow, but hopefully feasible, WTO reform continues to be discussed.

[1] Shaffer, G., & H. Gao (2018), ‘China’s rise: how it took on the US at the WTO’, University of Illinois Law Review, 2018/1, p. 115-184.

[1] Garcia-Herrero, Alicia, & Gary Ng (2021), ‘China’s State-Owned Enterprises and Competitive Neutrality’, 23/II/2021.