Theme: Despite having recently initiated negotiations to join the EU, Serbia has declared itself neutral concerning EU sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine crisis. This paper looks at Serbia’s somewhat ambiguous position between the EU and Russia.

Summary: The conflict in the Ukraine has revived the logic of the Cold War. Since the EU’s new borders have strengthened its eastern flank, limiting Russia’s room for manoeuvre, the Balkan countries have come back into the limelight. Serbia is a particularly interesting case in point. Despite having recently initiated negotiations to join the EU it has declared itself neutral concerning the EU’s sanctions against Russia. This paper focuses on the three main areas that determine the ambiguity of Serbia’s position: (1) the Kosovo issue; (2) the country’s relations with NATO; and (3) its economic-energy relations with Russia and the EU. Serbia’s behaviour seems to be driven by the logic of maximising its gains and using Russia as a way of maintaining the EU’s interest in enlargement. However, the problem is the sustainability of this policy in the near future, especially if the conflict in the Ukraine intensifies. Bearing in mind Serbia’s interest in joining the EU, its politicians should seize the opportunity to open a national debate about the three areas mentioned above and discuss the realistic options open to the country. At the same time, the EU should support Serbia’s efforts by making integration in the EU a real –and attainable– goal for it.

Analysis

Introduction

President Obama’s statements guaranteeing the protection of the Eastern European countries that feel threatened by Russia appears to be leading Europe back to the re-establishment of the old bloc system. If EU enlargement to the east has served to safeguard Europe’s eastern flank, the focus should now be on the countries stuck in the middle. At a time when geopolitics are back on the agenda, the situation of the Balkans should return to the limelight. Despite being at some distance from the hotspot, their poor economic situation and their remaining unresolved conflicts make them the weakest part of Europe. As the cold war experience has shown, in a world of blocs every country counts and the logic of attracting allies is again being developed by both sides.

In this context, Serbia is in particularly interesting situation: it has declared itself neutral in the conflict over the Ukraine alleging that its national interests are at stake and it has refused to join the EU in imposing sanctions on Russia. Such a position is perceived by the EU as paradoxical for a country that has recently opened up negotiations to join it. Nevertheless, national interests, mainly determined by energy dependency, explain not only the country’s behaviour but also that of many others in Europe (with Germany at the top of the list). Thus, the main question concerning Serbia is not its right to legitimately defend its national interests but the ambiguity of its willingness to integrate into what is still perceived in some sectors as the ‘West’. Despite the open manifestation of Serbia’s desire to be the next country to join the EU, its ties to Russia seem to be becoming even stronger. This is not merely a theoretical dilemma since it translates into governmental decisions and policies that have practical repercussions.

Had the crisis in the Ukraine not occurred, the ambiguity could have remained ‘unresolved’ while negotiations with the EU proceeded. However, the Ukraine crisis has changed the paradigm in Europe, reviving the old ‘friend-enemy’ scenario. This geopolitical outcome explains the increased attention (and high level official visits) that Serbia is receiving from both sides. It also presages a growing pressure on the country, particularly since it will hold the OSCE chairmanship next year. In this context, maintaining a neutral policy could be extremely delicate and any false step could ruin Serbia’s efforts on its path to EU integration.

This paper focuses on the three main areas that determine Serbia’s position concerning Russia and the triangle it forms with the EU: (1) Kosovo and its impact on Serbian foreign policy; (2) the country’s policy towards NATO; and (3) its economic relations, particularly in the field of energy. Serbia has made remarkable progress on its path to joining the EU, but it seems to be exploiting uncertainties in order to maximise its gains in its negotiations with both sides. The question that remains is the sustainability of this policy in the near future, as the country is highly dependent on the development of events in the Ukraine. Under these circumstances, Serbia could use the Ukraine crisis to trigger a nation-wide debate to reach a consensus on strategic issues, such as Kosovo, NATO and the extent of its relations with Russia and the EU, which will determine its future. At the same time, it is the moment for the EU to be more pro-active and to adopt a more strategic policy towards Serbia, showing that it can understand the latter’s difficult position. In this respect, EU enlargement should be a genuinely open door.

Belgrade on the chessboard

This year several important meetings have taken place in Belgrade. The most recent was Vladimir Putin’s visit to commemorate the city’s liberation in 1944. At the beginning of May Belgrade also received the simultaneous visit of the President of the Russian Parliament, Sergey Naryshkin (one of the Russian officials sanctioned by the US), and the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policy, Stephan Füle. The following are extremely helpful to understanding the factors inherent in the triangle formed by Serbia, Russia and the EU.

- The political elite is divided as regards Serbia’s orientation towards Russia or the EU. Füle was received by Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić –known for representing the government’s pro-European faction– while Naryshkin was received by the President Tomislav Nikolić –known for his pro-Russian slant–. The pro-Western and pro-Russian divide is entrenched in the political class despite all political parties currently in Parliament being in favour of EU integration. It is also present in the population: according to the latest poll, 50% are in favour of joining the EU and 70% of closer relations with Russia. However, when asked to whom Serbia should give priority, 27.8% answered Russia, 14.1% the EU and 51% were in favour of having good relations with both.

- Russia is using history to inflame anti-Western and pro-Russian feelings. The commemorations of WWI and WWII this year are particularly meaningful for both countries since the most important symbols of solidarity between them are drawn from those wars. They are interpreted by Russia as a sign of the expansionist and bellicose policy that characterise the Western powers, with the Ukraine crisis just being a further episode. From the Serbian side, Russia’s support concerning the interpretation of the WWI is extremely valuable since there are revisionist opinions that point to Serbia as the main culprit of the Great War.[1] Narishkin’s agenda included a visit to the monument to those killed by the NATO bombings of 1999. This sensitive issue is the cause of anti-western feeling and is repeatedly used by Russia to express its commitment to Serbia. ‘NATO aggression angered Russian society’[2] as Naryshkin pointed out during the visit. Putin also seized the opportunity to stress Russia’s unchanged position on Kosovo.

- Serbia is committed to joining the EU. While Putin and Naryshkin were dealing with history, European officials were praising Serbia for its efforts on Kosovo and its ambition to join the EU before 2020. Although the EU’s representatives have publicly declared that Serbia is not obliged to adhere to its sanctions against Russia (European laws only contemplate such an alignment at later stages of the negotiation process) it seems very likely that the message to the Serbian government is quite different. In fact, there is a real concern in pro-European circles about the impact this could have for Serbia: for the first time Chapter 31, devoted to foreign policy, could become an obstacle to integration.

Secondly, the natural catastrophe that affected Serbia in mid-May, which caused human casualties and extremely severe material damage,[3] was a further occasion for displaying power and influence. The Russians responded effectively and rapidly, despatching rescue teams and humanitarian aid. For its part, the EU –although less quickly off the mark– raised €995 million at an international donors’ conference in addition to providing €60 million from its solidarity fund. Nevertheless, the image of Russian soldiers rescuing victims was used by the media to exemplify the close relations between the two countries.

Finally, the increasing attention that Serbia is receiving from both the West and Russia is the best indicator of the changes that Europe is experiencing. By the end of this year Serbia’s Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić will have met representatives of Germany, France, Russia and China. Moreover, the First Conference on the Western Balkans,[4] which took place in Berlin on 28 August, shows the interest of the EU, and especially Germany, in securing the region’s South-East. This interest can translate into opportunities for business and investments, as needed by the region.

Increasing attention and the opportunities arising from it might have changed Serbia’s perception and strategy. More confidently, Serbia has started to develop a policy of ‘blowing hot and cold’ that is a result not only of cultural-historical factors but also of a pragmatic strategy to maximise gains. The following section analyses the interaction of the various factors behind Serbia’s options.

The Kosovo question and Serbian foreign policy

The status of Kosovo and its unilateral declaration of independence in 2008 have been the main factors determining Serbia’s foreign policy over the past decade, with two main effects:

- An obstacle to its entry to the EU. Serbia’s foreign relations after the war, as defined by its Minister of Foreign Affairs Goran Svilanović (2001), were based on four pillars: its return to the international community, EU membership as its main objective,[5] the balance of power between the US, Russia and China, and the restoration of relations with the non-aligned countries. However, in 2008 the independence of Kosovo caused a political earthquake that led to a ‘degradation’ of the goal of EU membership. While EU membership was maintained at a declaratory level as one of Serbia’s priorities, other questions, such as territorial integrity and military neutrality, emerged to put the EU integration process on hold.

- Its rapprochement with Russia. Russia’s rejection of Kosovo’s declaration of independence and its veto at the UN Security Council, along with its request of an advisory opinion on the legality of this action by the International Court of Justice, were the two main actions that facilitated Serbia’s rapprochement with Russia. Hence, from 2008 on, the two countries have increasingly cooperated by coordinating their positions on international issues and by signing a series of agreements covering economic, strategic and foreign affairs issues,[6] which will be analysed below. Serbia’s neutrality on events in Georgia and Abkhazia (2008) and the Ukraine are an instance of its new alignment.

This situation stagnated until a new government came into power in May 2012. Surprisingly, the new government, led by the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) and drawn from the ranks of the nationalist Radical Party, marked a turning point in the country’s policy towards Kosovo and EU integration. In May 2013 Belgrade and Prishtina initiated a process to normalise their relations and in January 2014 Serbia officially opened negotiations in order to join the EU. This highly risky political move was put to the test at the snap elections in 2014 that gave an absolute majority to the SNS, with voters not only showing their willingness to join the EU but also their readiness to turn the page on Kosovo by ignoring the parties that more strongly refused to talk to the EU outside Parliament.

It is generally assumed that Serbia’s progress towards EU integration is determined by its parallel progress towards a solution for Kosovo. This explains the government’s behaviour in two different ways, which could be construed to be contradictory: first, in its determination to integrate Kosovo’s Serbs into its political structure and, secondly, in its adamant refusal to accept Kosovo’s independence. However, the logic seems to be that keeping Kosovo’s status on hold is the best way of maintaining the EU’s interest in Serbia’s integration, so that it will only consider the ratification of Kosovo’s independence at the end of the membership negotiation process. This interpretation is particularly consistent in a context in which the enlargement process is highly unpopular and is only justified before the EU for geopolitical reasons. In current circumstances, Russian support is necessary for the development of this strategy, since its withdrawal could jeopardise Serbian efforts to maintain a comfortable leeway to negotiate on Kosovo.

Serbia’s position on NATO

Serbia is the only country in the Balkans that is neither a NATO member nor a candidate to join. Its position is based on the ‘Resolution of the National Assembly on the protection of sovereignty, territorial integrity and constitutional order of the Republic of Serbia’ whereby it has declared military neutrality. In more specific terms, the declaration of military neutrality must be understood as the official rejection to entering NATO although not ruling out participation in several of its programmes. The Partnership for Peace (PfP) signed in 2006 has led Serbia to carry on a process of reforms and modernisation in its defence sector and to update it in accordance with NATO standards[7] with the aim of participating in international crisis management actions.[8] The Alliance’s increasingly important role was confirmed in 2010 by the approval of the Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP), which included not only technical issues but political dialogue as well.

Nevertheless, Serbia’s rapprochement with NATO was parallel to its engagement with Russia in the field of Security and Strategic affairs. In fact, 2013 was a key year for the enhancement of Serbian-Russian cooperation: the two countries signed a Strategic Partnership in May and a Bilateral Agreement on Military Cooperation (which took 15 years to be reached) in November. Additionally, Serbia became a Permanent Observer of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). According to analysts, the content and scope of these agreements[9] in no way challenge Serbia’s cooperation with NATO and even less constitute an alternative to it. However, they are seen as deliberate acts that show Serbia’s willingness to maintain the best relations it can with Russia (regardless of its EU integration process) and Russia’s interest in blocking any attempt to join NATO, in line with its ‘red line’ policy.

In this context, Serbia’s position is determined by several factors:

Nonetheless, it should be borne in mind that Russian opposition has not prevented other Balkan countries from showing their interest in becoming members of NATO. The most remarkable instance is Montenegro: despite a similar aversion to NATO,[10] it received a Membership Action Plan in 2009 as its Prime Minister, Milo Đukanović, had integration as one of the country’s main foreign policy objectives. Moreover, although its has very strong economic ties with Russia, last year Montenegro refused to allow the establishment of a Russian military base at Bar (Tivar), planned to be an alternative emplacement for the only military base Russia has in the Mediterranean, at the Syrian port of Tartous.

Since South-Eastern Europe is far from its ‘natural area of interest’, Russia did not consider the steady move of these countries towards the EU and NATO as a major threat. However, the current situation in the Ukraine could make Russia strongly re-consider its position. In this respect, the example of Montenegro is again particularly pertinent since its candidacy to join the Alliance has been put off until 2015. This answer to Montenegro’s request has been interpreted by analysts as an indication by NATO that it does not wish to fuel a confrontation with Russia, but at the same time has left Montenegro in the lurch and open to possible reprisals. At any event, the West’s lack of a long-term geostrategic vision could have a very negative effect on countries like Serbia since it can discourage a more defiant policy towards Russia.

- NATO’s intervention against Yugoslavia in 1999. The memory of the 78-day bombing operation that caused the death of 2.000 people and displaced thousands is still very much alive in Serbia. In 2013 only 13% of the population supported NATO membership (compared with 53% supporting EU membership). This explains the lack of interest among politicians to push the issue and the scant publicity that Serbia’s participation in NATO programmes has received. Nevertheless, it is also clear for Serbia that NATO plays an important role as the only international force (KFOR) entrusted with ensuring the security of Kosovo’s Serb population. During an interview last February with Bruce Naples, head of the NATO Joint Force Command, the Serbian Minister of Defence, Nebojša Rodić, said that KFOR is the most trusted international actor in Kosovo and underlined the importance of not downsizing troop numbers.

- Russia’s position concerning NATO. In accordance with the ‘red-line’ policy, in December 2013 the Russian Minister of Defence, Sergei Shoigu, met the then-Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, to ask him openly about the country’s position on NATO. After being assured of Serbia’s military neutrality and its intention never to become a member of the Alliance, the two countries finally signed the defence cooperation agreement mentioned above.

- The legacy of Yugoslavia. Following the logic of Yugoslavia’s geostrategic position in the Cold War, whereby its status as a non-aligned country was an opportunity to be courted by both sides, being the only non-NATO member in the Balkan Peninsula can be interpreted by Serbia as a threat but also as an opportunity. Serbia is an excellent candidate to be Russia’s regional ally[11] because the latter’s position in the Mediterranean is threatened by the conflict in Syria while the conflict in the Ukraine has polarised Eastern Europe and its traditional allies –Bulgaria and Montenegro– are no longer available due to their commitment to NATO. Thus, the joint construction of an emergency centre at Niš in south-eastern Serbia in 2010, aimed at assisting Serbia and other countries in the Balkans in the event of natural disasters and emergency situations, has allowed Russia to gain a base on the ground, which is commonly held to be an excuse for it to be present in the region. In fact, the centre’s diplomatic status was one of the conditions to be negotiated during Putin’s visit to Belgrade last October, although it was finally removed from the agenda following strong pressure from the West. At the same time, having good relations with both NATO and the EU –in line with the principle of military neutrality– means that it cannot be accused of being anti-western.

On the other hand, Serbia’s neutrality can be very useful in the context of reaching an agreement on the Ukraine crisis. Since Serbia will hold the chairmanship of the OSCE from January of next year, its neutrality and the trust it inspires in Russia could serve to facilitate an agreement.

Serbian trade relations and energy cooperation

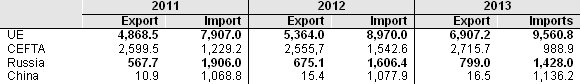

Despite the image of Russia as Serbia’s closest partner, in terms of trade relations, the EU and regional structures (such as CEFTA)[12] are by far its most important partners. In Europe, Italy and Germany are in the lead while the EU is also Serbia’s main source of Foreign Direct Investment, at 78.4%.[13]

Table 1. Serbia’s main economic partners, exports and imports (€ million)

Source: EU Delegation in Serbia.

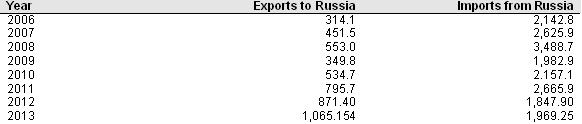

As for Russia, in 2013 bilateral trade reached US$3,034 million (see Table 2). In terms of exports, Russia stands in fifth position, at 7.6%; in imports it is Serbia’s third-largest partner, at 9%.[14] Energy remains the main import from Russia (60%), whereas exports are dominated by agricultural products.

Table 2. Serbia-Russia bilateral trade (US$ million)

Source: J. Simic (2014), “Economic aspects of Strategic Partnership between Serbia and Russia”, The New Century, nr 6, Belgrade, February, p. 22-32.

Economic relations between Russia and Serbia are governed by a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) signed in 2000, which covers 99% of bilateral trade. The agreement is important for Serbia not so much for the actual volume of trade between the two countries (given the different size of their markets, Serbia cannot fully develop the possibilities) as for the attractiveness that it offers foreign investors and companies –it is the only FTA that Russia has signed with a south-eastern European country and, moreover, the only one outside the Commonwealth of Independent States. In addition, Russia and Serbia have developed a wide range of cooperation agreements in different areas (tourism, health, banking and joint activities related to medium and small enterprises) and several loans have been granted (totalling US$800 million) to renew the country’s railway system.

During Putin’s visit to Belgrade he said that Russia was prepared to increase agricultural imports from Serbia up to €500 million (from the current €200-300 million). Nevertheless, this is a poisoned gift as the increase would occur in the context of EU sanctions against Russia. Last summer Belgrade was already warned by the European Commission against using sanctions to increase exports to Russia. So such a move would be perceived as disloyal, leaving Serbia in a difficult situation with its EU partners.

Serbian-Russian energy cooperation

If Russia’s relevance in terms of economic exchanges is relatively moderate, the bulk of its relations with Serbia is based on energy, since Russia is its main provider of natural gas. In this area the two countries have signed several agreements and conducted some important joint projects:

- In 2008 they signed a cooperation agreement for the oil and gas industry whereby Gazprom bought 51% of Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS), Serbia’s state-owned oil company.[15] Talks on the South Stream project began in the same year.

- In 2011 the construction the Banatski Dvor underground gas storage facility, a joint venture between Gazprom and Srbijagas, was completed.

- In 2013 Serbia and Russia agreed to undertake the reconstruction of the Novi Sad oil refinery and established a programme to increase the processing of oil derivatives at the Pančevo refinery, involving an investment of € 1.5 billion over the following two years.

Nonetheless, the most important deal concerning both countries is the South Stream pipeline. This project, extremely influenced by the political environment in Europe,[16] has been one of the Serbian government’s priorities. It involves €2 billion in Foreign Direct Investment for the country and the creation of 2,500 jobs during the construction period. Moreover, it will turn Serbia into a gas transit and storage centre for Europe.[17]

Map 1. The South Stream pipeline: Serbian section

Source: South Stream Serbia.

The confrontation between the European Commission and the Russian government over its non-compliance with European Law[18] has halted the project several times. In this respect, Serbia is in a special position since it is the only transit country which is not an EU member but is nevertheless a member of the European Energy Chapter Treaty on the adoption of EU energy legislation. The EU Commission has warned Serbia that it could also be penalised in the event of an infringement of EU Law.

In this context, several high-level meetings between Russian and Serbian delegations have taken place this year. The most important was held on 7 and 8 July in Moscow when the Serbian Prime Minister, Aleksandar Vučić, met his Russian counterpart Dmitri Medmedev and the Russian President, Vladimir Putin. Before the meeting, the Serbian media had echoed several requests[19] that were to be presented to the Russians, among them a reduction in the price of gas (currently established at €400/1,000m3).

Despite all the rumours concerning the visit, especially about a hypothetic ultimatum to Serbia in order to gain its support in the Ukrainian crisis, the meetings were mainly focused on economic issues [20] and more particularly on South Stream. In fact, at the same time that the meetings were taking place in Moscow, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergei Lavrov, was in Bulgaria and Slovenia (7-8 July) to solve the impasse concerning the South Stream negotiations. During a previous visit to Belgrade last June, Lavrov had already asked Serbia not to give up[21] on the South Stream project, particularly after the announcement of the suspension of work on the project in Bulgaria.[22]

The agreements on the South Stream project with Serbia seem useful for Russia in at least two ways. First, politically, to show that it is not alone at a time when the West is trying to ostracise it. Secondly, to promote South Stream at all costs now that the conflict in the Ukraine presages a future full of obstacles. As long as the project remains at risk and Serbia can help Russia reach its objectives, it is very likely for the latter not to put too much pressure on the former to take sides in the Ukraine conflict.

Nevertheless, it is important to underline here that some days after Putin’s visit to Belgrade, Russia cut its gas deliveries by 30%. The official reason was an unpaid debt owed by Serbia to Russia totalling US$200 million. An unofficial explanation suggests that the cause was the investigation launched to evaluate the legality of the process under which Serbia sold NIS to Gazprom in 2008. It has also been said that it was a way of punishing Serbia for leaving out of the agenda of Putin’s visit the agreement on the humanitarian centre at Niš and any official act to launch the South Stream works. In any case, it was a strange move in a country in which Putin enjoys wide popularity. However, it does suggest that, should the time come, Russia would not hesitate to use all means to put pressure on Serbia.

On the other hand, should the South Stream problems finally be resolved, the EU should be very conscious of the fact that Serbia would be the pipeline’s only non-EU transit country. Taking into account the current situation in the Ukraine, energy security in Europe should be one of the factors to be considered at the next EU enlargement round.

Conclusions: Serbia seems determined to join the EU, with its strong economic relations with the Union and the dialogue process with Prishtina being the best examples of its interest and commitment. At the same time, Belgrade continues to foster its privileged dialogue with Moscow. Three factors determine its position towards Russia. First, its cultural proximity. Any alienation from Russia would be incomprehensible to the population since –unlike for other countries in Eastern Europe– Russia has always been considered an ally by the Serbians rather than as a threat. Secondly, Serbia needs Russian support to complete its policy shift towards Kosovo. If Belgrade were to lose Russian support its negotiating position would be substantially weakened. This would hamper not only one of the main incentives for integrating Serbia in the EU but also harm its image as a key actor to end the conflict –which is important for internal political reasons–. Finally, in the current context of crisis in the Ukraine, Serbia exploits its double allegiance to maximise its gains by maintaining the EU’s interest in the integration process while receiving favours from parties in terms of military cooperation, energy, investment and trade.

Bearing in mind Serbia’s interest in joining the EU, even if Belgrade maintains its neutrality towards Russia it could seize the opportunity to initiate a national debate in which politicians should be clear about realistic alternatives on the various issues at stake: Kosovo, military neutrality, EU integration and its interests concerning Russia. This would help society re-organise its national project and would also be an important political sign for Serbia’s European allies. On the other hand, the EU –and the West in general– should provide Serbia with more support without giving the impression of blackmailing it with EU integration. In this respect, it is critical to show that EU enlargement is a real possibility, not just an empty promise.

Raquel Montes Torralba

Specialist in political science

[1] ‘World War I History divides Balkan Schoolchildren’, Balkan Insight, 6/V/2014.

[2] ‘State Duma speaker Sergei Naryshkin: “we are increasingly confronted with attempts to shift the blame on the victims with the aggressors”’, RU Facts, 5/V/2014.

[3] The damage assessment so far is: 60 casualties, 32,000 evacuees and thousands of millions of euros in material damage.

[4] ‘Final Declaration by the Chair of the Conference on the Western Balkans’, Berlin, 28/VIII/2014.

[5] This objective was pushed forward at the Thessaloniki Summit in 2003 between the EU and the Western Balkans in, at which they were declared ‘potential candidates’ to the EU.

[6] Z. Petrovic (2010), ‘Russian-Serbian Strategic Partnership: Scope and Content’, in Z. Petrovic (Ed.), Russia-Serbia relations at the beginning of the 21st century, Isac Fund, Belgrade, p. 25-40.

[7] M. Nic & J. Cingel (2014), ‘Serbia’s relations with NATO: the other (quieter) game in town’, CEPI, January.

[8] In January 2014 Serbia had 213 peacekeepers on six UN missions, its largest contingents being posted in Lebanon and Cyprus. Serbia also participates in EU missions in Somalia/Uganda and in the EU NAVFOR Operation Atalanta to combat piracy in the Indian Ocean.

[9] Z. Petrovic (2010), ‘Russian-Serbian Strategic Partnership: Scope and Content’, in Z. Petrovic (Ed.) (2010), op. cit., p. 25-40.

[10] K. Rekawek (2013), ‘The western Balkans and the Alliance: All is not well on NATO’s Southern Flank?’, The Polish Institute of International Affairs, nr 14 (62), June, p. 5-6.

[11] A. Fatic, A., ‘Serbia’s Strategic Dilemma- Between NATO and Russia’, in M. Kosic & M. Karagaca (Eds.), New Serbia, new NATO: Future vision for the 21st century, TransConflict Serbia, Forum For Ethnic Relations, Klub 21, Belgrade, p. 223-226.

[12] Central European Free Trade Agreement. Members: Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Serbia and the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo on Behalf of Kosovo.

[13] EU Delegation in Serbia.

[14] J. Simic (2014), ‘Economic aspects of Strategic Partnership between Serbia and Russia’, The New Century, nr 6, Belgrade, February, p. 22-32.

[15] It is frequently stressed that these agreements were reached in parallel to Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence (February 2008) and with Russia’s contrary vote at the UN Security Council.

[16] C. Oliver & J. Farchy (2014), ‘Russia’s South Stream gas pipeline to Eutope divides EU’, Financial Times, 4/V/2014.

[17] ‘South Stream comes to Serbia’, Gazprom, 24/XI/2013.

[18] ‘South Stream bilateral deals breach EU Law’, Euractiv, 4/XII/2013.

[19] According to the media, Serbia had three requests: to increase oil and gas income; to reduce the price of gas; and the authorisation to export 10,000 Fiat 500L (through the extension of the free trade agreement). Source: ‘Vicica u Moskvicekaultimátum’, Informer, 3/VII/2014.

[20] The Serbian delegation comprised the Minister of Energy, Aleksandar Antić, the Minister of Economy, Dušan Vujović, and the Mayor of Belgrade, Siniša Mali.

[21] ‘Lavrov reassures Serbia on South Stream’, EurActiv, 18/VI/2014.

[22] B. Lewis (2014), ‘EU asks Bulgaria to stop work on Gazprom’s South Stream pipeline’, Reuters, 3/VI/2014.