Original version in Spanish: Elección presidencial y reforma energética se citan en Argelia

Theme

This paper reviews the pre-electoral economic and energy contexts in Algeria and explores the virtues and limitations of the ‘energy spring’ narrative of the new Algerian energy sector authorities.

Summary

In recent months there have been more announcements of an imminent hydrocarbon law and progress has been made in improving Algeria’s relations with international oil and gas companies, with several contracts having been extended or renovated. Nevertheless, it appears that the introduction of substantive reforms will have to wait for the outcome of the 2019 presidential elections.

Analysis

Introduction

Against all expectations, 2018 has been a relatively untroubled pre-electoral year in Algeria. The rise in oil prices has considerably eased the country’s economic situation and the budget has been given a social focus with the reversal of some of the adjustment measures applied in previous years. The expansive fiscal election cycle has also been underpinned by the Central Bank’s financing of public debt. In the spring of 2018, a year ahead of the presidential elections in April 2019, much publicity was even given to a number of direct interventions by President Bouteflika to correct decisions of the Ouyahia government. From an economic perspective, he has insisted on popular measures like the need to reverse subsidy reductions, halt the increase in ID and passport issuing costs and prevent the sale of agricultural land to foreigners. In the political field, he dismissed the chief of police, Abdelghani Hamel, who –like many others– happened to be a possible presidential candidate.1

He has also taken similarly assertive action in the energy sector with, for instance, a presidential decree to increase his power to appoint senior Sonatrach staff and to reinforce the authority of the company’s new Chairman. The new team responsible for energy policy, appointed in 2017, has spent months attempting to transmit a narrative of an Algerian ‘energy spring’. Even if modest from a European perspective, it is an opportunity for greater openness and deserves some encouragement. Although not quite a ‘petroleum perestroika’,2 it does seem to suggest a greater willingness to reform and an increased flexibility in the face of a changing global energy environment. This analysis will first look at Algeria’s overall economic context and then on the hydrocarbon sector, focusing on the indications in recent months of a possible increased openness.

Pre-election economy

If the narrative of an ‘energy spring’ is still premature, applying it to Algeria’s broader economic policy is simply inappropriate (other than in reference to the season’s usually unsettled weather). The tension between reformists and conservatives in Algeria gives rise to decisions that are contradictory, subsequently corrected or ultimately abandoned and therefore in a wildly erratic economic policy.3 The 2018 budget was far removed from the relative discipline of previous years, and the rise in oil prices has aggravated the electoral fiscal cycle. This is confirmed by the 2019 budget proposal (Loi de Finances) presented at the end of September: a close to 8% rise in public spending, particularly current expenditure –and, within that item, social transfers–, continued recourse to monetisation of the fiscal deficit and, of course, not a single new tax or cut in subsidies.4

Figure 1 shows Algeria’s main economic indicators, along with their recent and projected performance. First, economic growth fell from 3.7% in 2000-15 to only 2% in 2017. According to IMF projections growth will rebound in 2018 as a result of the pre-election fiscal expansion and the recovery in oil prices, whose effects will persist through 2019, although not as strongly. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) expects slightly lower growth rates for 2018, but with an upturn beginning in 2019 due primarily to the rise in oil prices and the coming on stream in the next few years of the most recent investments in the gas sector.5

The cost of having maintained growth with counter-cyclical measures during the years of low oil prices shows in the deterioration of the country’s main macroeconomic balances. Inflationary pressure, contained until 2015, will push inflation in the next few years above 7%, with a resulting rise is discontent among a population already beset by rising prices. Conversely, the recovery in oil prices could reduce the bulky public deficit recorded in 2015 and 2016 of over 15% of GDP to 7% by 2018. This substantial budget deficit stemmed from the increase in social transfers, which the 2018 budget has raised by 8% to account for total 9% of GDP. Should the 2019 budget proposal be approved, social transfers would rise to 21% of the budget and foreseeably again expand as a percentage of GDP.

After the increase in current expenditure estimated for 2018, the public deficit should again drop to below 5% of GDP. This would slow down an escalating debt, set to rise from 8.8% of GDP in 2015 to above 30%. The data relating to the Algerian Treasury’s recourse to the Central Bank was released in June and, as expected due to fiscal expansion, was above the Finance Ministry’s target. Nevertheless, there was no further monetisation after February, showing that fiscal emergencies have receded as a result of higher oil and natural gas prices.

In the external sector, after the ending of the enormous surpluses recorded in the years of high oil prices, the recent price recovery will allow the current account to be rebalanced: from a deficit of over 16% of GDP in 2015 and 2016 it should drop below 10% from 2018. Foreign currency reserves should continue to decline, although at a slower pace and always with a relatively comfortable margin to cover over a year’s imports. The EIU expects slightly more favourable estimates for 2018 and slightly more favourable forecasts for subsequent, especially a faster rebalancing of the public deficit to around 6% of GDP in 2018.

These projections, estimates and forecasts are clearly very sensitive to oil price fluctuations. The penultimate row in Figure 1 shows the fiscal breakeven oil price, ie, the price of oil required to achieve budgetary balance. Between 2000 and 2016 the Algerian budget required average oil prices of over US$100/barrel to maintain a balance. The (modest) fiscal adjustments of 2016 and 2017 achieved a certain effect by reducing the fiscal breakeven price from US$102/barrel to US$86. The election budget cycle should raise the fiscal breakeven price to close to US$106, to subsequently decline to around US$84 in 2019, more in line with oil price forecasts (although the estimate is prior to the expansive budget proposal for 2019). It should be borne in mind that oil companies do not expect oil prices to be much above US$80/barrel, but they do require investment projects to be profitable at prices of only US$50. For the sake of prudence, hydrocarbon mono-producers and their public companies should therefore adopt a reasonably similar framework. Figure 1. Algeria: main economic indicators

| 2000-14 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 (1) | 2019 (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real GDP growth (%) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| Inflation (CPI, %) | 3.7 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 7.6 |

| Public deficit (% of GDP) | 2.9 | -15.7 | -13.5 | -7.1 | -8.2 | -4.8 |

| Public debt (% of GDP) | 24.8 | 8.8 | 20.6 | 25.8 | 33.3 | 38.4 |

| Current account balance (% of GDP) | 11.4 | -16.5 | -16.6 | -12.3 | -9.3 | -9.7 |

| External debt (% of GDP) | 15.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Foreign exchange reserves (months of imports) | 26.9 | 28.4 | 22.6 | 19.0 | 16.2 | 13.4 |

| Fiscal breakeven oil price (US$) | 102.1 | 106.8 | 102.5 | 86.7 | 105.7 | 84.3 |

| External breakeven oil price (US$) | 70.2 | 84.5 | 73.4 | 74.5 | 76.8 | 76.6 |

(1) Forecasts.

Source: IMF, Regional Economic Outlook Update: Middle East and Central Asia, May 2018, Statistical Appendix.

In general, the macroeconomic scenario reflects the inconsistencies of economic policy. Although the government has tried to adjust to a lower oil price environment, the election cycle has only partially allowed it to do so. The recourse to unconventional financing of the budget deficit raises serious questions over the middle term, as highlighted by the World Bank.6 Now that the narrative of ‘lower for longer’ appears to have proved to be wrong, the short-term incentives to maintain fiscal discipline could become even weaker.

Volatility has also had its effect on 2018’s microeconomic policy. An area of particular interest to Europe (and Spain) is trade policy. Since 2015 Algeria has applied one protectionist measure after another, significantly affecting commercial relations with the EU. The Algerian rationale is to contain the balance of payments deficit, but there is also a clear element of political economy: incumbents aim to protect the rent generated by licences, tariffs and bans typical of protected markets.

Algeria first paralysed the trade liberalisation foreseen in the Free Trade Agreement of the Algerian-EU Association Accord. Then it introduced discretionary import licences on products like vehicles and cement and other construction materials. From 2018 licences are no longer applicable to vehicle imports, but further restrictions have been introduced, including the halt to imports of various product groups covering some 850 tariff line items, increased tariffs on around 130 additional line items and further administrative and financial requirements.7

As explained below regarding the energy sector, the economic context prior to the elections has been marked by a temporary improvement due to the oil price rise. The problem is that the window of opportunity for fiscal adjustment and microeconomic reforms created by the rise has come at the same time as the run-up to the elections. The two factors combined reinforce the temptation to continue banking on a continued price recovery and avoiding or minimising reforms. But as with the energy sector, a relatively more favourable situation for the election cycle in the short term should not obscure the many economic challenges facing the country in the medium and long terms.

Gas and prices to the rescue

Contrary to other hydrocarbon mono-exporters, such as Venezuela, Algeria’s economic policy has not been so poorly managed as to prevent it from benefiting from the current rising trend in oil prices.8 The worst-case scenarios considered in 2014, when prices started to drop sharply, have not materialised. Neither has there been a return to the instability of the black decade of the 1990s or a coup d’état, as in Egypt.9 On the other hand, in line with expectations, the country continues to mark time while President Bouteflika’s succession remains unresolved. Because of this, economic policy-making continues in a context of slow but sure deterioration as it awaits more favourable political and economic circumstances.10

It was a risky gamble, and largely taken by default, given the political unviability at the time of engaging in tough fiscal adjustments and thorough microeconomic reforms. The bet was partly based on the hope of oil prices eventually recovering, but also on something more tangible: the entry into operation of new gas projects than can temporarily reverse the country’s declining production.

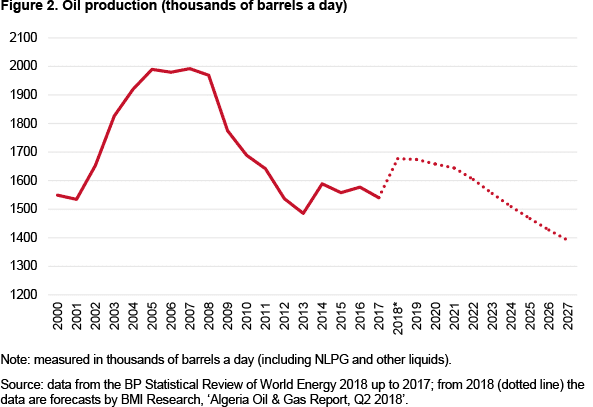

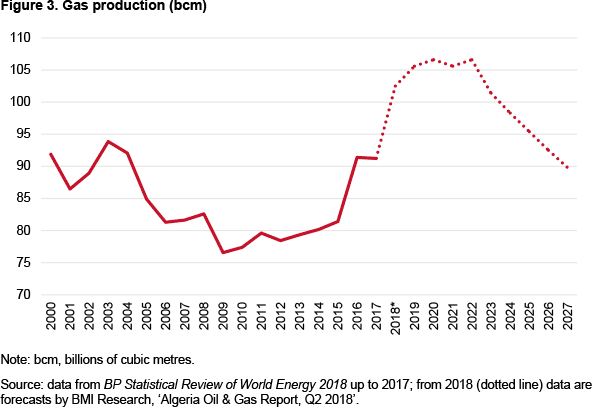

Figure 2 shows how Algerian oil production has stagnated in recent years and the decline expected over the medium term. With all due caution regarding the various forecasts, the short-term trend for gas production, shown in Figure 3, is more favourable. After the swift drop in production during the 2000s and the stagnation recorded in the first half of the current decade, production rose significantly in 2016 (but not in 2017) and further increases are expected as projects currently underway are completed and come on stream. In the case of gas, production is not expected to decline until the beginning of the coming decade, although all the increases registered during the period will be a thing of the past by 2027. While the possibility of President Bouteflika making endless future re-election bids cannot be ruled out, it is Algeria’s immediate election that is the more urgent concern.

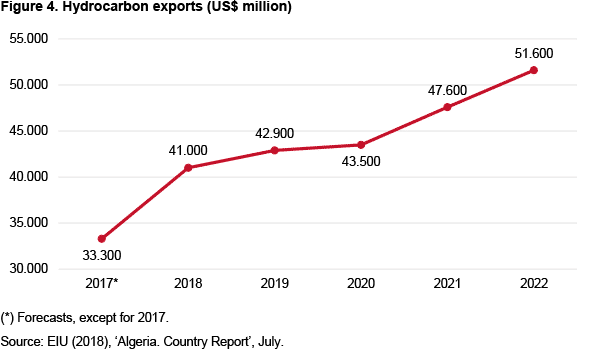

Before the 2018 pre-election year, oil prices again began to rise, boosting the country’s export income. Figure 4 shows the forecasted increase in hydrocarbon export earnings up to 2022, driven by the increase in both gas production and oil prices. As with the expected decline in gas production, the problem arises in 2022. Regardless of the trend in oil prices, Algeria needs to undertake the gas investments necessary to reverse the expected production decline.

However, it is advisable to regard the optimistic projections for Algerian gas production with a degree of scepticism.11 For instance, to include the production of shale gas is clearly premature, as explained below. The forecasts shown in Figure 3 depend on how production develops at the Hassi R’Mel field, particularly in winter when temperatures drop and gas is reinjected. Although Algeria has so far been able to fulfil its contracts, in 2017 it was unable to supply France with any additional quantities of gas. Some forecasts are so pessimistic that they consider no Algerian gas exports by 2030 under a scenario of high domestic demand, as has already occurred in Egypt.12 More importantly, even the most favourable projections are only optimistic in the short term, suggesting a very difficult scenario from 2023-24 onwards.

Similarly to the economy, the recent improvement in the Algerian energy sector indicators and projections cannot mask the challenges it faces in the short and medium terms. Considering how long it takes to develop gas projects, particularly in Algeria, investments should be undertaken as soon as possible. But the truth is that in recent years unfavourable contractual, fiscal and administrative conditions in Algeria have made it impossible to attract the necessary investments from international companies. The latest bidding rounds for exploration licences have been met with scant interest, with the country’s overall business environment seen to be highly discouraging.13 Indeed, further rounds have been indefinitely postponed and none are expected under the current regulatory framework.

Excessive red tape and long delays in approval, difficulties in operating in an erratic trade policy framework, obstacles to international flows (from financial to customs-related) and the security situation in general all raise the transaction cost of being in the country. Additionally, the tax system limits potential income by penalising extraordinary profits (ie, a windfall tax), adding a strong disincentive to the current market context. The limitation on foreign participation in projects (the so-called Rule 49/51 restricting it to 49%) is a further hindrance mentioned by foreign companies.

Finally, despite having some of the world’s largest reserves of unconventional (shale) gas, Algeria’s strategy for its exploitation has been equally erratic. According to various estimates, the country has the third or fourth largest ‘technically recoverable’ reserves, after the US, China and Argentina. The Ghadames Basin, extending from eastern Algeria to southern Tunisia and western Libya, is one of the world’s largest in terms of unconventional gas resources.14 But the advantages of favourable geological conditions and an established gas industry have so far been offset by technical, political and economic obstacles.

Concern about competition from fracking for a scarce resource like water –although played down by the industry, which is banking on further technological development– has given rise to violent protests in the affected localities in the southern part of the country (like those in In Salah in 2015 following the first perforations). On the other hand, the bureaucratic inefficiency and excessive red tape plaguing the development of conventional gas resources also affect shale gas.15 In a context of low prices and a hostile public opinion, those previously in charge of Algeria’s energy policy had as a priority the development of conventional gas reserves with lower production costs. Although they did not rule out exploiting shale gas, they decided to postpone it in the hope of more favourable conditions in the future, such as higher natural gas prices, more advanced technology to minimise costs and reduce the impact on aquifers and water consumption, and (linked to the latter) and a more amenable public opinion.

A late ‘energy spring’, of a limited character and yet to be confirmed

Given the lethargy induced by the political paralysis in the Algerian energy sector, in the spring of 2017 the government began to signal a change of course. The first step was to stabilise the situation at Sonatrach, paralysed by both corruption scandals and the rapid succession of five chairmen in barely seven years. The appointment of Abdelmoumen Ould Kaddour changed the trend. In 2007, Kaddour had been the subject of a shady plot devised by the then all-powerful intelligence services (Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité or DRS), which were later disbanded by Bouteflika in 2016. Accused of being in possession of DRS documentation, he was charged with espionage by a military court and sentenced to 30 months in prison in a hurried trial rife with inconsistencies. After 20 months in prison he was set free with no explanation thanks to the influence of someone in Bouteflika’s trust. He then moved to Dubai as a consultant.

In early 2017, presidential emissaries travelled to Dubai to visit Kaddour and managed to convince him –apparently with some difficulty– to take charge of Sonatrach.16 This was not just a personal rehabilitation for Kaddour himself, but also indirectly for his mentor, Chakib Khelil, Minister of Energy from 1999 to 2010, the real target of the DRS intrigues aimed at taking over control of Sonatrach.17 The fact that Khelil is one of the potential presidential candidates has given rise to a number of interpretations of Kaddour’s appointment. In June 2018 a presidential decree modified Sonatrach’s statute, granting new powers to Kaddour, essentially as regards making appointments to the board of directors. Nevertheless, it also strengthened presidential control over the company, whose chairman and deputy chairman would henceforth also be appointed by presidential decree. Sonatrach is close to completing the renovation of its management team and already has new directors for its major divisions (Strategy, Upstream, Pipeline Logistics and Commercialisation).

Around the same time, Arezki Hocini was made head of the National Hydrocarbon Resources Development Agency (Alnaft), the sector regulator. Hocini is close to Kaddour and Khelil and was the first to be rescued from oblivion by the regime, although in his case simply from mundane retirement. The new Energy Minister, Mustapha Guitouini, was previously at the distribution company Sonelgaz rather than being involved with upstream exploration and production; neither does he have a significant political profile, so until recently he has kept a low profile and barely intervened in extraction policy.

The new energy team immediately returned to the spirit of greater openness enshrined in the 2005 oil law promoted by Khelil but later curbed by measures such as the 49/51 rule and the windfall tax, which placed restrictions on foreign investment. In parallel, Alnaft seems to be in the process of extending its responsibilities, which –although no details have been released– may involve taking over some of Sonatrach’s historical regulatory and control functions, thus making it more commercially-oriented and comparable to other major international companies.

The stated aim was to revive the Algerian oil and gas sector with the backing of the presidential circle. To begin with, contact was re-established with the international companies to try to find an amicable solution to pending disputes and brush up its tarnished image. A year later Sonatrach was able to resolve 80% of its outstanding litigation, including its disagreements with Norway’s Statoil and the US company ExxonMobil.18 The most notable case was the partnership reached with Total, putting an end to a fraught history and returning to a climate of mutual understanding between the two companies.

Then came the signing of new contracts and the extension of others, among them several with Total. One of the agreements is a concession signed at the end of 2017 within a new legal framework between Sonatrach, Total and Alnaft to develop the Timimoun field.19 At the beginning of 2018 Cepsa, Sonatrach and Alnaft agreed on a further concession to exploit the Rhoude el Krouf (RFK) field, located in the Berkine Basin. Subsequently, in April 2018 Sonatrach signed an ambitious framework agreement with ENI to relaunch exploration and development in the same basin and to strengthen their cooperation in other areas of the energy sector (including shale gas, petrochemicals, renewables and offshore exploration).20 More recently, in June, another agreement was signed by Sonatrach, Total and Repsol to extend the Tin Fouyé Tabankort (TBT) gas-concession contract.

These initiatives were accompanied by a round of consultations with international oil companies to gather information on the measures that would be necessary to reform the Hydrocarbon law and make the sector more dynamic. Although a welcome novelty, the outcome of the consultations has not been made public and nor have the companies been informed whether their suggestions will ultimately be taken into account. This vagueness and lack of transparency are a further significant limitation to the past few months’ narrative of a more open energy sector. While international companies appear to have been led to believe that host government take (HGT, which in most cases is around 90%) will be reduced by the new Hydrocarbon law, they are discounting that it will continue to be too high.

Foreign policy adds a further layer of complexity. Thus, the success of the contracts signed with Total has partly been due to France’s aim of preserving its interests in Algeria. Meanwhile, it has continued to block the Midcat gas pipeline and the access by pipeline of Algerian gas to the rest of the European market. These strategic inconsistencies have a considerable impact on the prospects for Algerian gas exports to Europe.

The other remaining challenge was the renewal of gas supply contracts with Algeria’s main customers, many of which were close to expiration. The negotiations, of which little has been made public, had been stretching out for years with no visible progress. European companies, supported by the Commission, insisted on more flexible contract conditions, reducing their duration and the possibility of less rigid price indexation formulas, as Russia was already doing to adapt to the new far more competitive context of a more abundant supply of natural gas.21 Although the Algerian authorities showed some understanding, they countered by stressing the importance of security of demand and insisting on a certain stability of expectations.

In June 2018 Naturgy (previously Gas Natural Fenosa) became the first European company to renew its contract, ensuring its supply of Algerian natural gas until 2030. Although no details have been released, the terms appear to be more flexible, both as to time frame (10 years) and price formulas. Foreseeably, negotiations with all other clients –some enshrined in framework agreements like those between Sonatrach and ENI and Total– will follow the same format. While late, this is a welcome development that reveals an inkling of rationality in Algeria’s energy policy, fostering positive expectations about the long-announced new hydrocarbon law.

After a long wait and much rumour-mongering, on 4 June Kaddour announced a contract with the US consultancy firm Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle to provide advice on designing the country’s new oil sector legislation. He also stressed the need for it to be enacted and applied swiftly to ensure a better investment context and to attract the interest of international companies. This strategy appears to consist of the new law being approved with practical implementation mechanisms being adopted at the same time –contrary to 2005, 2006 and 2012, when the relevant decrees were delayed for years, paralysing the sector as a result–.22 Minister Guitouni, on the other hand, has expressed his disagreement for the first time and has showed his preference for a more cautious approach that could hinder the process.23

Something similar is happening with respect to the future of unconventional gas. Conscious that an increase in conventional gas exploration and production will be insufficient to offset the declining output at existing fields, the new Algerian energy sector authorities are again showing an interest in developing the country’s vast shale gas reserves. In recent months they have started talks with the US companies ExxonMobil and Chevron, although they seem to be at a very early stage and with a long-term prospect.24 Shale is also the object of the partnership with Eni and Total, although the negotiations that have made the most progress appear to be those with Anadarko and BP. In recent declarations to Bloomberg, Kaddour included among Sonatrach’s priorities both offshore exploration and what he termed ‘new energies’ (‘We don’t want to call it shale… I don’t like the term’).25

Given time constraints, none of these projects will see the light of day before the upcoming presidential election, thereby avoiding political costs during the campaign and allowing the government’s cautious stance to be maintained for a few more months. Given the difficulties facing conventional gas production, it is unlikely that shale gas will be any easier. Considering the difficulties faced by conventional production, it is unlikely for the development of shale gas to be any easier. To the contrary, its success would depend on maximum operational efficiency, which would require a favourable business, tax and regulatory framework that as of today is present almost only in the US: a smooth decision-making process, services companies that operate in a highly competitive market, technological development appropriate to each specific project and an uninterrupted flow of equipment and technical staff. For instance, equipment imported by international companies is held up by customs, on occasion by up to six months, which is plainly at odds with the speed required by the shale industry. In any case, the new law is expected to have a more favourable tax treatment for shale and offshore gas, as well as promoting the investigation of underexplored basins.

Conclusions

Algeria’s macroeconomic situation reflects the inconsistencies of its economic policy, further aggravated by the elections. Resorting to unconventional financing of the deficit and the recovery of oil prices have further weakened fiscal discipline in the run-up to the presidential election. The latter’s timing has reduced the window of opportunity for fiscal adjustments and reform that had been made possible by the temporary improvement in the economic context, masking the many economic challenges facing the country over the longer term. The hydrocarbon sector is in a similar situation. Improved conditions should not mask the absence of the investments that are necessary to reverse the decline in production. In addition to the excessive red tape hindering projects –from long delays in approval and execution to obstacles to international transactions– there is an unsatisfactory fiscal framework and a 49% limit on foreign participation in gas projects. Algeria’s shale gas strategy to date has been erratic and raises the same doubts that also affect the conditions for exploiting conventional gas.

To deal with these difficulties, the new Algerian energy-policy authorities have shown signs of being more amenable to reforms and laid the groundwork for the new hydrocarbon law and for a shift in policy as regards unconventional gas. In only a few months, Sonatrach, the national oil and gas company, has resolved a large number of its disputes and arbitration problems with international companies; it has signed new contracts and renewed or extended others with Cepsa, Eni, Naturgy (Gas Natural Fenosa), Repsol and Total; and it has also rekindled an interest in unconventional gas and sought support from US and European companies. The new hydrocarbon law, in the offing for years now, is probably a unique opportunity to culminate these efforts and provide a firm setting to attract the international investment needed to develop Algeria’s gas reserves. Sontrach’s Chairman and the hydrocarbon sector regulator have spent months resorting to a narrative of an Algerian ‘energy spring’, although certainly not with a name that is so uninspiring in the North African context.

However, the new slant in Algeria’s oil and gas policy does have certain limitations. This paper has highlighted red tape and lack of transparency as two of the main burdens weighing down the possibility of a more open energy sector (which are particularly critical to the shale industry), as well as the distortions caused by foreign policy considerations. Nevertheless, the conclusion is that the foremost limitation, as for the economy as a whole, is that the timing of reforms overlaps and is subordinate to the election cycle. Furthermore, red lines such as ‘49/51’ rule and an excessive host government take cannot be crossed before the process is over and only with a substantial degree of difficulty afterwards. This makes complicates and delays taking of decisions, prevents the employment of high-quality contractors, pushes back reaction times and undermines the attractiveness of the county’s energy sector to international investors.

The future of Algerian energy is one of the most important strategic issues to be settled by the 2019 presidential elections. After years of paralysis, energy reform is something that cannot be postponed much longer, but neither is it likely to be resolved before the country’s political situation is clearer. A sound energy sector reform not only needs a new law and its effective implementation but legitimacy and political authority. If, as seems likely, Bouteflika accedes to the parliamentary majority’s demand that he run for President again, an ambitious reform programme could become one of the key legacies of his fifth term in office. He will have to confirm, broaden or reverse certain important measures, starting with the hydrocarbon law and its associated implementation decrees, and only in the medium term will it be possible to devise a coherent strategy for exploiting unconventional gas reserves.

Gonzalo Escribano

Director of the Energy and Climate Change Programme, Elcano Royal Institute | @g_escribano

1 The Economist Intelligence Unit-EIU (2018), ‘Bouteflika’s rivals bide their time’, 18/VI/2018.

2 See ‘Les hydrocarbures pris en otage par la présidentielle de 2019’, Africa Energy Intelligence, nr 818, 5/VI/2018.

3 G. Escribano (2017), ‘Algeria: global challenges, regional threats and missed opportunities’, in K. Westphal & D. Jalilvand (Eds.), Political and Economic Challenges of Energy in MENA, Routledge.

4 H. Haddouche (2018), ‘Dépenses en hausse, planche à billets : une LF 2019 fortement influencée par la présidentielle’, Tout Sur l’Algérie, 27/IX/2018.

5 EIU (2018), Algeria. Country Report, July.

6 World Bank (2018), ‘Algeria Economic Outlook – Spring 2018’, April.

7 European Commission-High Representative (2018), ‘Rapport sur l’état des relations UE-Algérie dans le cadre de la PEV rénovée’, SWD(2018) 102 final, 6/IV/2018.

8 G. Escribano (2018), ‘Argelia no es Venezuela’, Elcano Expert Commentary, nr 22/2018, 4/IV/2018.

9 G. Joffé (2015), ‘The outlook for Algeria’, IAI Working Papers 15/38.

10 G. Escribano (2016), ‘A political economy of low oil prices in Algeria’, Elcano Expert Commentary, nr 40/2016, 19/X/2016.

11 H. Darbouche y J. Hamilton (2015), ‘North Africa’s energy challenges’, in Y. Zoubir & G. White (Eds.), North Africa Politics. Change and Continuity, Routledge.

12 A. Aissaoui (2016), ‘Algerian Gas: Troubling Trends, Troubled Policies’, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Paper NG 108, May.

13 Algeria is 166th (of 185 countries) in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2018 ranking (http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018).

14 US EIA (2013), ‘Shale gas resources: an assessment of 137 shale formations in 41 countries outside the United States’, June, updated 24/IX/2015.

15 T. Boersma, M. Vandendriessche & A. Leber (2015), ‘Shale gas in Algeria. No quick fix’, Brookings Energy Security and Climate Initiative Policy Brief 15-01, November.

16 F. Alilat (2018), ‘Algérie: Ould Kaddour, de la prison à la tête de Sonatrach’, Jeune Afrique, 15/I/2018.

17 In June 2018 Kaddour said in an interview that the entire affair had been concocted by the DRS ‘pour casser Chakib Khelil’. See Y. Babouche (2018), ‘Ould Kaddour: “J’ai été jugé pour espionnage alors que BRC avait construit le siège de l’état-major de l’armée!”’, Tout Sur l’Algérie, 3/VI/2018.

18 ‘Sonatrach a réglé 80% de ses litiges’, El Watan, 7/III/2018.

19 ‘Cepsa, Sonatrach, Total y Alnaft firman un nuevo marco contractual de la concesión del campo de gas de Timimoun’, Cepsa press release, 13/XII/2017.

20 World Oil (2018), ‘Eni and Sonatrach strengthen cooperation in the gas sector in Algeria’, 18/VII/2018.

21 Essentially reducing contract time frames from 20 or 25 years and agreeing on indexation formulas with higher weightings for the prices of European hubs.

22 African Energy Intelligence, op. cit.

23 EIU ViewsWire (2018), ‘Algeria economy: quick view – US firms hired to advise on hydrocarbon law’, 7/VI/2018.

24 Natural Gas World (2018), ‘Sonatrach eyes foreign investors for shale gas: CEO’, 6/VII/2018.

25 Sonatrach CEO Kaddour on Oil Supply, Prices, Investment, Bloomberg Markets and Finance, 24/IX/2018.