Summary

The 2024 edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index confirms the recovery of the pace of growth of globalisation after the pandemic. However, unlike previous years, post-pandemic globalisation has taken on a harsher character, with greater emphasis on the economic and especially the military dimensions, while the soft power dimension has declined. Compared with the previous year, the global presence of Russia, China and India has increased significantly, whereas that of the US and the major European countries has decreased.

In recent years, the value added by the global presence of countries in the so-called Global South has grown, while that of countries in the Global North has stagnated or even declined. Despite this growth, the gap between the two groupings remains considerable, comparable to that of the mid-1990s.

Spain has increased its global presence in absolute terms over the past year, unlike most European countries, allowing it to gain market share and maintain its position in the ranking. Compared to pre-pandemic years, and not yet reflecting the recovery of international tourism, the importance of manufacturing exports has risen, while the significance of services and foreign investment has decreased in Spain’s projection. Within the soft dimension, Science and Technology have gained prominence, while Tourism, Culture and Development Cooperation have diminished.

Analysis

The outbreak of the pandemic in 2020 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have intensified the debate about the future of globalisation.[1] This debate had already been sparked by the crisis of 2010, given its impact on European countries and the gradual reduction of their global presence since then. It was further fuelled by the paralysis of major international organisations and particularly by the transformation of the multilateral trade framework due to the return of bilateral protectionism between the US and China. The trend had already been reflected in previous results of the Elcano Global Presence Index.[2] This tool was created to contribute to the analysis of international relations through a methodological proposal for measuring the volume and evolution of the globalisation process, as well as the terms of external insertion of the 150 countries for which it is calculated.[3]

1. A harder globalisation

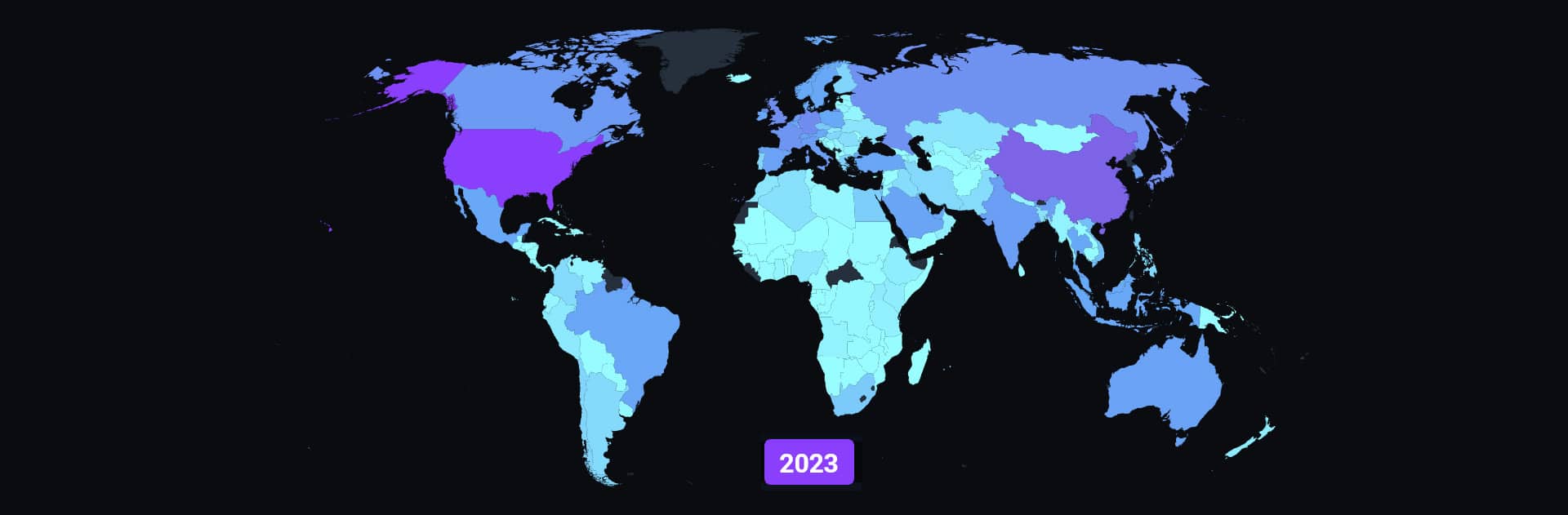

The results of the 2024 edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index confirm the reactivation of the globalisation process after the pandemic. The aggregate value of the global presence of all the countries for which it is calculated resumes its growth rate and reaches the maximum level so far estimated in this 2023 edition (see Figure 1).

The recovery is driven by the substantial growth of the military dimension, heavily influenced by the deployment of Russian troops in Ukraine and the remilitarisation trend among Asian countries. In an inflationary context of energy and primary goods, the economic dimension is also expanding, although modestly compared with the military dimension. It is important to note that, with the data considered for this edition, the recovery of international tourism is not yet reflected, significantly limiting the growth of the soft dimension. Nonetheless, between 2022 and 2023 all countries have seen an increase in the number of tourists received, except for China, Ukraine and Cameroon, although the numbers are still below pre-pandemic levels.

Since the 1990s the globalisation process has undergone different stages in terms of the intensity of growth and the dimensions that have guided it. As shown in Figure 2, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, globalisation was characterised by a strong growth in the economic dimension, as well as the demilitarisation of international relations. The 2000s marked the highest growth in globalisation, driven by the full integration of China and the consolidation of regional integration processes, which sustained the momentum of economic globalisation and also facilitated the growth of the soft dimension.

The decade of 2010 was heavily influenced by the impact of the crisis, particularly affecting European countries, which have since significantly reduced the value of their global presence. However, the growth of the soft dimension continued, ultimately supporting the globalisation process during these years.

Thus, the pandemic, which particularly affected indicators of the soft dimension related to the international mobility of people, significantly affected the aggregate global presence. As of today, the soft dimension still registers a lower value than in 2019, while the economic and military dimensions have recovered their growth. It should be noted that this only considers three years since the pandemic, whereas the previous periods comprise decades, so the growth rate of the economic and military dimensions is not at all low considering that it has already reached half of the growth recorded in the entire previous decade.

Therefore, the growth rate of globalisation is recovering after the pandemic, as indicated by the aggregate value of global presence. However, it is a harder globalisation, meaning it is more economic (in an inflationary context), more military (in the context of the Ukraine war) and less soft (with some indicators not recovering).

Within the top 20 positions in the 2023 Global Presence Ranking (see Figure 3) there are three significant changes compared with the previous year. First, Russia rises one position to 6th place, overtaking France; secondly, India gains two positions, while South Korea and Italy drop one position; and, thirdly, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE advance by two and one positions, respectively, leaving Singapore to drop by two positions.

In fact, in absolute terms, Russia is the country that increases its global presence the most compared with 2022 (see Figure 4), due to the significant increase in its military presence with the number of troops deployed in Ukraine –Russia is now the country with the most troops deployed outside its borders–. The second greatest increase in presence over the last year is in China, although the magnitude is considerably lower than in previous years. Energy exporting countries also increase their presence significantly, given the current inflationary context. Among European countries, setting aside Norway, due to it being more like the former group, Spain is the European country with the greatest increase in global presence, followed by the Netherlands and Poland. Conversely, the US recorded the largest decline in presence compared with 2022, followed, though at a much greater distance, by Japan, Germany, the UK and France.

These results seem to confirm the hypotheses that the globalisation process is in a moment of transition, not only due to the slowdown in its growth but also due to the change in its key players, with an apparently increasing importance of an emerging Global South versus a declining North.

2. A not-so Global South

Indeed, in order to measure growth in the Global South, we can calculate its aggregate evolution.[4] First, it is worth noting that this is a hybrid concept, not necessarily bound by geographical or historical considerations, not entirely novel[5] but gaining relevance as a geopolitical reality in recent years in international relations studies.

There is still a significant difference between the two groups (see Figure 6), which in 2023 was slightly less than that recorded in 1990. It is indeed true that since the 2010 crisis, the growth of presence for Northern countries –particularly European ones– has notably slowed down, while the growth of the South –particularly China– has accelerated. And this trend has intensified since the pandemic, with a loss of presence in the North and strong growth in the South, partly due to the inflationary context of energy and commodity goods, which strengthens the presence of primary-exporting southern countries.

Hence, if we consider the evolution of the economic presence (see Figure 7), the above diagnosis is further intensified. The impact of the 2010 crisis on the economic presence of the North intensifies, while a strong growth in the economic presence of the South is recorded in recent years. Indeed, the geographical region with the greatest growth of presence last year was North Africa and the Middle East. Additionally, it is important to note that a significant portion of the aggregate evolution of the economic presence is determined by what happened in the Investment indicator. In this respect, developed countries have recorded significant losses in this indicator over the past year (-20.5% in the US, -10.6% in the UK, -9% in Canada and -8.4% in Germany).

Considering the evolution of the Military Presence (see Figure 8), the results are very different. First, there was a noticeable trend of demilitarisation in international relations in the 1990s. But 2010 marked a significant turning point, after which Northern countries continued to record a gradual loss of military presence, while Southern countries reversed the trend. In 2023 both groups registered practically the same value, with the difference being minimal. Additionally, it is worth noting that the North obviously includes the US, which holds the top position in the military ranking every year. Excluding it, the military presence of the South would be higher than the North’s.

This trend is primarily explained by the indicator of Troops Deployed abroad, and to a lesser extent by the indicator of Military Equipment, where there is still a considerable gap. The significant increase of troops deployed in Ukraine –Russia currently has the highest number of troops deployed abroad in the world– and, on the other hand, the remilitarisation process in Asia-Pacific for the past few years, contribute to understanding this evolution. Additionally, there has been an increasing participation of various Southern countries, particularly African nations, in the UN’s peacekeeping missions.

In the soft dimension (see Figure 9) there remains a notable gap. The Northern countries continued to grow after the 2010 crisis and the difference with the South is greater today than in 1990. However, the South has shown a greater dynamism in the soft dimension in the last decade, consequently reducing the gap. Within this dimension, there is a greater heterogeneity in the evolution of countries in each indicator. For example, in the Science indicator, there is a widespread reduction in Southern countries, except for China, which increases by 15% in this indicator, widening the gap with the US and Europe.

Obviously, the trend among groupings is determined by the evolution of the results of the main countries within them. Three ideas stand out: (1) there is a sustained loss of presence of European countries and of the EU as a whole, with a sharp decline in 2023; (2) despite the US managing to maintain a global presence share amidst the Asian rise,[6] in recent years the pace of its growth has slowed down, even resulting in a global presence loss in 2023; this is also reflected in a decline in presence share, which is now nearly at the minimum level recorded in 2012; and (3) China’s presence keeps growing and reaches its maximum in 2023, but growth is progressively slower. All in all, the gap has been considerably reduced. The difference in 2023 between the global presence share of the US and the EU with China was 7 and 6.5 percentage points, respectively. This difference was 17 and 15 percentage points, respectively, in 2005.

3. Spain: resilience in the global context

In 2023 Spain maintained its 13th position in the Global Presence Ranking. As mentioned above, it is one of the few developed economies that recorded absolute increases in global presence over the past year. Amidst the broader context of the increasing presence of Southern countries and the declining presence of European ones and of the US, Spain has managed to slightly boost its share of global presence.

By dimensions, Spain recorded a significant growth in its economic presence last year, although it dropped to 17th place from 15th position it held the previous year. This was due to the strong growth of the economic presence of Russia and the UAE, driven by the rising prices of energy goods. Spain also increased its military presence, moving up to 12th place, while its soft power presence remained almost constant, at 16th.

The pandemic had a particularly significant impact on the evolution of Spain’s global presence. The importance of the tourism sector has historically influenced the terms of Spain’s external insertion, with a significant role played by service exports in the economic dimension and tourism in the soft dimension. Therefore, the interruption of international mobility significantly reduced its external presence.

Some years after, when comparing Spain’s external integration profile before and after the pandemic, there are significant changes. It should be noted that, as was the case with the rest of countries, the data included in the current edition do not reflect the recovery of international tourism. This has two direct implications on Spain’s presence profile. The first is that it has not yet regained the main feature of its external projection in the past, which was its strong capacity to attract tourism. The second is that, as a result, within its economic profile, the full recovery of service exports has not been achieved, given the importance of tourism services among them. However, the recovery of the latter is notably superior to the former, indicating the growing relevance of non-tourism service exports and evidencing the gradual transformation of Spain’s tertiary profile. By dimensions, there is no change in the relative importance of each one on Spain’s presence value –with a 63.5% economic presence, 14.1% military and 22.4% soft– but there are significant changes in the prominence of the indicators (see Figure 10).

In the economic dimension, the Manufacturing, Primary Goods and Energy indicators have gained relevance, influenced by the inflationary context. Conversely, Services, particularly as related to tourism, and Investments –in line with the general trend–, are the indicators that registers the greatest relative loss. So, while maintaining the same overall economic presence, Spain has transitioned towards a profile less focused on services and investments and more on the export of goods.

In the military dimension, the Troops indicator has gained weight, given the current maximum of Spanish troops deployed abroad. On the other hand, the Military Equipment indicator has decreased in significance.

In the soft power dimension, the importance of the historical features of Spain’s global projection, such as Tourism, Culture and Development Cooperation, has diminished. Meanwhile, indicators like Technology, Science and Climate Change have gained prominence, reflecting a shift in Spain’s soft presence profile.

Conclusions

The 2024 edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index confirms the resurgence of the globalisation process after the pandemic, but with a noticeable shift towards a harder line, in the economic and military dimensions, while soft presence is on the decline. Over the past year, there has been a significant increase in the presence of countries such as Russia, China and India, while the US and the main European nations have declined.

The aggregate presence of the so-called Global South is on the rise, fuelled by the evolution of countries in South-East Asia, particularly China, but also India, Russia and primary-exporting regions in the current inflationary context. On the contrary, the North has experienced a stagnation or even a decrease in the added value of its global presence, a trend that has accelerated after the pandemic. Despite this, the difference between the two groupings remains significant and similar to that recorded in the 1990s in the economic and soft dimensions, but not in the military one, where the gap has significantly narrowed.

In this context, Spain stands out for its adaptability and growth. Unlike most European countries, it has managed to recover the growth of its global presence in absolute terms over the past year, maintaining its position in the global ranking. The importance of manufacturing exports and energy products is growing, while services and the volume of investment abroad have decreased. There are also significant changes in Spain’s soft profile, with a reduction in historical indicators such as Tourism and Culture towards Technology, Science and Climate Change. These are positive signs of Spain’s adaptive capacity despite the turbulent global environment.

[1] Iliana Olivié & Manuel Gracia (2020), ‘The end of globalisation? A reflection on the effects of the COVID-19 crisis using the Elcano Global Presence Index’, ARI, nr 43/2020, Elcano Royal Institute, April.

[2] Iliana Olivié & Manuel Gracia (2023), ‘(Re)globalisation after the pandemic: analysis of the results of the Elcano Global Presence Index 2022’, ARI, nr 61/2023, Elcano Royal Institute, April.

[3] Iliana Olivié & Manuel Gracia (2023), Global Presence Index. Methodology, Working Paper, nr 4/2023, Elcano Royal Institute.

[4] The Global South is considered to comprise Latin America, Africa, Asia (excluding Israel, Japan and South Korea) and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), as well as Russia and the republics of Central Europe.

[5] This concept was already present in the writings of Gramsci, in the dependency theory of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and in the world-system approach, and gained momentum in the postcolonial world of the 90s. See N. Dados & R. Connell (2012), ‘The Global South’, Contexts, vol. 11, nr 1, p. 12-13.

[6] For a more detailed analysis of the evolution of the global presence of the US up to 2022 and its geographical distribution, see Manuel Gracia & Iliana Olivié (2024), ‘Tracking alliances in a fragmented and geopolitical world: the US according to Elcano Global Presence Index’, ARI, nr 20/2024, Elcano Royal Institute, February.