Theme

The Italian elections of March 2018 –which have become a case study for populism– have caused much anxiety in Europe; as a founder member of the EU, Italy deserves a deeper analysis to understand its electoral dynamics.

Summary

Italy has been in the news for a long time. With a complicated party system under frequent change, economic instability, the return of its long-standing problem of corrupt politicians and a new electoral law, it has been suggested that Italy is the Eurozone’s ‘Achilles heel’. Being the first major European election of 2018, there are many aspects to discuss. After decades of being immersed in political corruption, Italy has seen the emergence of the Five Star Movement (M5S) as one of the most powerful anti-establishment political parties in Europe, so the election results are likely to generate much scholarly work. However, it is very important to understand Italy’s economic and social dynamics in order to better understand its election processes. The reactions to the existing economic scenario, with widespread discontent, the insoluble north-south divide, irregular immigrant flows and a lack of confidence in the country’s democratic institutions have led to a point where it appears that mainstream politics have failed. Nevertheless, before reaching a simplistic conclusion, it is worth the effort to try to understand Italy, looking at its economic indicators in times of crisis while unravelling the issues concerning the trust of the people in their institutions. Thus, this paper analyses the election results and suggests some recommendations related to the future of both Italy and European integration.

Analysis

Introduction

Italy’s legislative election was one of the remaining obstacles to the reform of the Euro, the country being the third largest in the Eurozone. Many European scholars and decision makers have been awaiting the results with curiosity, in an attempt to estimate future moves more clearly. Being held on the same day as the Social-Democratic vote on the Grand Coalition in Germany, this has been a very important election for the future of Europe. Italy has been led by a caretaker government since the failed constitutional referendum in 2016. The predictions were clear, with the country divided into three: the Five Star Movement (M5S), the centre-right bloc led by Silvio Berlusconi –including the League– and the centre-left led by the Democratic Party (PD). What was not clear was each one’s share of the vote. Furthermore, following the failed constitutional referendum of 2016, the election was a test run for the new electoral system, the so-called Rosatellum bis of 2017, in which almost 37% of the seats are allocated using a first-past-the-post system and the rest using a proportional method, also including the seats allocated to Italians abroad.

This paper first looks at Italy’s economic indicators, which may help to gauge the current situation. Then it analyses the trust indicators and compares them to other southern European countries. All this provides a framework to better understand the election results of 4 March 2018. Before concluding, it comments on the results of the election and speculates on the possibilities of a coalition, since the result has been a hung parliament.

Italy’s economic indicators

The economic crisis in Europe has mostly affected the continent’s southern countries. With very high levels of unemployment in addition to increasing inequality, the resulting social change and unrest have been unavoidable and have also affected their current party systems. In some cases, the change has been sharper than in others. Italy, historically a multiparty system country, has had its fair share of change. The disappointment regarding the economy helps explain the anger felt by Italian society and the wish to penalise the mainstream political parties. Italy’s main economic indicators since 2004 are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Economic indicators in Italy since 2004

| Year | Unemployment rate | Youth unemployment | Government debt-to-GDP | GDP growth rate | Gini coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 8.0 | 23.5 | 100.1 | 1.6 | 32.9 |

| 2005 | 7.7 | 24.1 | 101.9 | 0.9 | 32.7 |

| 2006 | 6.8 | 21.8 | 102.6 | 2.0 | 32.1 |

| 2007 | 6.1 | 20.4 | 99.8 | 1.5 | 32.0 |

| 2008 | 6.7 | 21.2 | 102.4 | -1.1 | 31.2 |

| 2009 | 7.7 | 25.3 | 112.5 | -5.5 | 31.8 |

| 2010 | 8.4 | 27.9 | 115.4 | 1.7 | 31.7 |

| 2011 | 8.4 | 29.2 | 116.5 | 0.6 | 32.5 |

| 2012 | 10.7 | 35.3 | 123.3 | -2.8 | 32.4 |

| 2013 | 12.1 | 40.0 | 129.0 | -1.7 | 32.8 |

| 2014 | 12.7 | 42.7 | 131.8 | 0.1 | 32.4 |

| 2015 | 12.7 | 40.3 | 131.5 | 0.8 | 32.4 |

| 2016 | 11.9 | 37.8 | 132 | 0.9 | 33.1 |

| 2017 | NA | NA | 134.7 (Q1) | NA | NA |

Source: the author, based on Eurostat.

To put things into perspective, prior to the crisis Italy was a low-productivity and low-growth country. As a giant in terms of the size of its economy and its government debt, Italy was singled out as the weak link in the European economy and the euro. As shown in Table 1, Italy had a massive debt-to-GDP ratio of 102.4% in 2008, being equal to over €1.6 trillion according to Eurostat (Eurostat, 2016). Additionally, it had low GDP growth and a chronic government-deficit problem. One of the reasons why Italy is a low-growth country with a huge debt ratio is that it is economically divided into two regions. As is well known, the north is highly industrialised and produces high-income competitive commodities for the export market; meanwhile, the south has low productivity, small or family firms and mostly agricultural producers. According to the September 2015 report of the Italian statistics agency (ISTAT), the difference in per capita GDP between south and central and northern Italy is so sharp that it is as much as 43.7% lower in the former.1 Hence, the Italian government has to transfer resources from the north to the south to offset the deficit.

Another reason for Italy’s high debt is its long-standing tradition of tax evasion and its thriving underground economy. In order to understand the dimension of tax evasion in Italy, it is sufficient to look at the ISTAT reports that claim that one of every four Italians, or around 15 million people, failed to report any taxable income in 2011. Even former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi was accused of tax dodging and famously said that ‘evasion of high taxes is a God-given right’ (Bhatti et al., 2012). In parallel to this, the same trend can be seen more clearly in Italy’s underground economy statistics. According to ISTAT, the Italian underground economy was valued at between 16.3% and 17.5% of GDP, totalling €275 billion in 2008. In 2013 the figures were still 11.9%, or €190 billion. The total non-observed economy (the underground and illegal economies) in the same year accounted for 12.9% of GDP, amounting to €206 billion (ISTAT, 2015).

Demography is a further problem. Italy has an aging population: in 2010 20.4% was aged over 65, compared with the EU-289’s 17.5% average. The projected old-age ratio (between the projected number of persons aged over 65 and the projected number of persons aged between 15 and 64) was 31.2 in the same year and is projected to be 49.9 by 2040 (Eurostat, 2016). This raises the question of how Italy intends to pay the interest on its long-term bonds while the economically-active proportion of the population becomes increasingly smaller and the ratio of the economically dependent becomes steadily bigger.

In summary, before the crisis, Italy’s massive debt load was perceived to be sustainable since Italian governments were traditionally able to pay interest repayments. However, the risk of contagion from other countries, given the fear that Italy’s lack of potential growth in the near and long terms would prevent it from covering its debts. In 2011 Italian 10-year bond yields were over 7%, a similar borrowing cost to those that triggered bail-outs in Greece, Portugal and Ireland (Henningsen, 2012). Even in the aftermath of the crisis, an article in The Economist named Italy’s banks ‘Europe’s next crisis’, underlining the extensive loan burden that, apparently, cannot be handled in 2016 (Economist, 2016).

In Italy’s case, the crisis gave rise to a turbulent political environment that resulted in a change of government approved by the EU in order to implement the necessary reforms. The new ‘technocratic’ leader, Mario Monti, was assumed to be a ‘guarantee in a political system characterised by high polarisation and hyper-partisanship’ (Verney & Bosco, 2013). In effect, the EU wanted to manage all these risks while effectively interrupting Italian democracy. Thus, it is important to put into perspective the country’s economic indicators along with aspects such as the trust in institutions in order to properly understand its electoral dynamics.

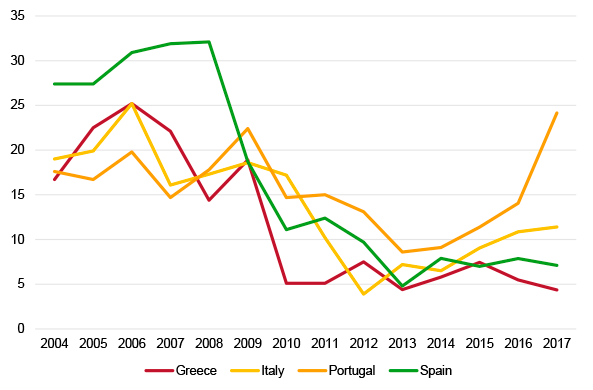

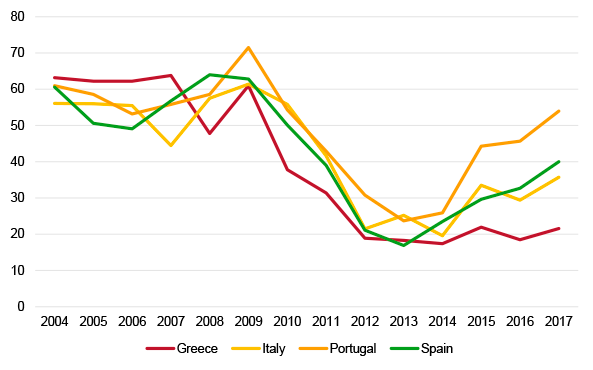

Trust in democratic institutions

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, trust in democratic institutions at both the national and European levels has recorded a significant decline in Italy. The figures are important to understand the disenchantment with politics and the rise of anti-establishment parties and, although the focus here is on Italy, the same can be said of all southern European countries. What is specific to the Italian case, and not reflected in the graphs, is the parallel disappointment with the functioning of legal institutions, such as courts and other administrative bodies. Adding the historical problem of the mafia into the equation, what has emerged is an enormous sense of frustration with democracy itself. This is even more visible in the south of the country, which is further afflicted by an endemic economic malaise. All these factors should be borne in mind when trying to understand Italy’s election results.

In particular, trust in political parties in Italy is very low, making competition difficult for the mainstream political parties. This sense of frustration partly explains the rise of the Movimiento 5 Stelle as the most-powerful anti-establishment political party in the country.

As shown in Figure 3, trust in the EU also recorded a decline, with the Union’s management of the economic crisis causing a high level of a discontent. The numbers help understand the Eurosceptic discourse now adopted by political parties. It is clear that anti-Europeanism has been ‘selling’ well for obvious reasons, while the argument of ‘taking back control’ has mobilised an anti-euro discourse. Although these trust-related indicators have been very similar in all southern European countries, their impact on political parties and party systems have not been the same. For this reason, it is important to have a look at the history of electoral dynamics in Italy, which helps understand the results even better.

The history of electoral dynamics in Italy

The Italian case is striking since the EU essentially ‘forced’ a change in government by placing excessive pressure on Silvio Berlusconi, which finally led to the appointment of a technocrat, Mario Monti, as Prime Minister for 2011-13. While no new elections had been called, the country’s main economic policies were decisively changed.

The severe austerity measures enforced by the technocrat Monti led to mass protests similar to those occurring in other parts of Europe. On 15 October 2011, as in other countries, tens of thousands of people gathered in Rome to protest against the austerity measures and the Troika’s political influence. The demonstrations continued over the following years, as with the ‘No Monti Day’ in October 2012, again protesting the unpopular measures implemented by the government, and the student protests against austerity cuts in education funding in November 2012. Finally, elections were called for 2013 with Italians returning to the polls to elect a new Prime Minister.

Before looking at the actual results, it is important to comment on the background of the political party that gained the highest percentage of votes. Disaffected voters frequently turn against the existing mainstream political parties and support independents or anti-parties, such as the Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S), founded in October 2009 by the popular comedian and blogger Beppe Grillo. M5S rejects ideological labels and claims to be neither on the left nor on the right. It advocates direct democracy on the grounds that the state has become disengaged from its citizens, supporting free Internet access and online participation in public meetings to make debate accessible to all as an alternative to representative democracy. In that respect, M5S identifies itself as a people’s movement and not as a political party, functioning as an intermediary between citizens and political elites. The Italian party system had hitherto been characterised by the two traditional left- and right-wing coalitions –respectively, Partito Democratico (PD) and Il Popolo della Libertà (PdL)– until M5S entered the political arena. The two traditional parties had gained 70.6% of the total vote in the 2008 election. But in February 2013, their combined vote fell to 47%, while at 25.6% M5S became the leading political force, ahead of both the PD (25.4%) and Forza Italia (formerly PdL, 21.6%) (Nordsieck, 2016). An important reason behind M5S’s success as an anti-party in the political system might be that both PD and PdL supported Monti’s technocratic government when it was implementing highly unpopular reforms and austerity measures in the months before the election. As a result, Italian voters may have decided that the two main options in Italy’s political system, regardless of their ideology, both shared responsibility and were equally powerless to confront an economic crisis. Thus, the importance of ideological considerations might have become a secondary consideration when voters evaluated their choices, which might have helped M5S since it distanced itself from both ideological labels (Vegetti et al. 2013).

The election of 4 March 2018

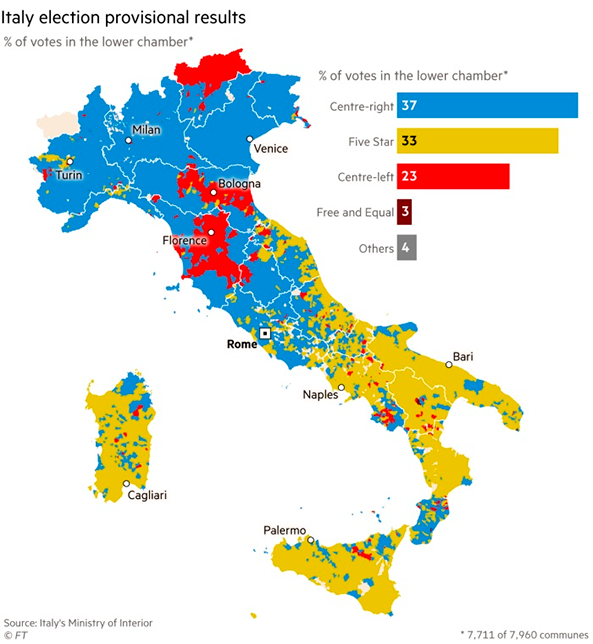

According to the polls, M5S was to be the most voted single party, bearing in mind also that both left and right competed as part of blocs. What is surprising is the difference between the first and second most voted political parties. Furthermore, turnout was 73%, slightly less than in 2013 but also a clear sign of how important the elections were considered to be. As shown in Figure 4, the PD reflected the gradual decline common to social-democratic parties throughout Europe. Nevertheless, in the Italian case the decline is very much connected to the party’s leader, Matteo Renzi. His ambition of holding a referendum without the necessary consensus in 2016 led to his resignation and significantly reduced his popularity. Thus, the decline in support for the PD is also attributable to this factor.

Figure 4. Italy’s legislative elections, 2003 and 2013

| Abb. | Name in Italian | Name in English | Party category | % 2018 | % 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M5S | Movimento 5 Stell | Five Star Movement | Anti-corruption politics Direct democracy Environmentalism | 32.66 | 25.6 |

| PD | Partito Democratico | Democratic Party | Social democracy Christian left | 18.77 | 25.43 |

| LN | Lega (Nord) | (North) League | Regionalism Right-wing populism | 17.37 | 4.09 |

| FI | Forza Italia (Il Popolo della Liberta) | Forward Italy | Liberal conservatism Christian democracy | 14.01 | 21.06 |

| FDI | Fratelli d’italia | Brothers of Italy | National conservatism | 4.35 | 1.96 |

| LEU | Liberi e Uguali | Free and Equal | Democratic socialism | 3.38 | – |

| +E | +Europa | More Europe | Liberalism | 2.55 | – |

| NCI | Noi con L’Italia | Us with Italy | Christian democracy Liberal Conservatism | 1.3 | – |

| SC | Scelta Civica | Civic Choice | Liberalism | – | 8.30 |

Note: only parties above the 3% threshold or bloc partners with vote shares above 1% cent are included.

Source: vote percentages are from official website of the Dipartimento per gli Affari Interni e Territoriali and party categories are from the Parties and Elections Database.

Looking at the overall situation, the right-wing bloc (Forza Italia, together with the extreme-right wing parties The League and Brothers of Italy and the centrist Noi con L’Italia) obtained the largest share of total votes, despite being insufficient to govern. The point to underline is that the League gained more votes than Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. For that reason, the candidacy of the European Parliament’s President, Antonio Tajani, was questioned, since Matteo Salvini was actually the most voted leader on the right. Time will show whether a coalition on the centre-right is possible, despite having gained only 37% of the vote.

In the leftist bloc (led by Matteo Renzi, together with the pro-Europe +Europa, Civica Popolare and Insieme) the numbers simply fail to add up. The only way that the PD can aspire to govern is through a possible coalition with M5S, leading to what could be called a different type of left-wing coalition. At any rate, even if opposed by Renzi, a possible coalition between the PD and M5S could open up a new era in Italian politics.

Both Matteo Salvini and the leader of the M5S, Luigi Di Maio, see themselves as the elections winners, lection, which will make them want to sit at any negotiations and take part in the bargaining, despite M5S having rejected any pre-electoral agreements. The tricky point is that neither has ever governed at the national level and they have always been in the opposition. Success in policy making could be a new test for all anti-establishment parties. The major decision now for the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, will be to decide who takes up the role of seeking to assemble some sort of coalition. Historically, in Italy the most voted party has always been included in the resulting government. Time will show if this will be a case of another historical first.

Last but not least, for the future it is important to consider the country’s electoral map and note the sharp contrast between north and south. It is clear that M5S mobilised the concerns of the citizens in the south and managed to convert them into votes.

In any case, Italy’s 3% threshold has let in several political parties, although none have a majority to establish a government. For this reason, over the coming weeks there will be much bargaining behind closed doors but it remains to be seen whether the country will end up with a coalition or minority government or if its –by now weary and frustrated– citizens will have to return again to the ballot box.

Conclusions

It will take time for Italy’s hung parliament to work out a coalition that can govern the country. Even if this is the case, a snap election will remain another plausible option. In the meantime, it is important to put into perspective the relation between the Italian elections and European integration, in order to avoid future crises. There are various issues to highlight. First, Italy has had difficulties in meeting the EU’s expenditure requirements and has for some time been cast in the role of scapegoat. The economic crisis of 2008 did not help to improve the situation. One of the important election pledges of the right-wing political parties was to ‘take back control’ of the economy. For this reason, in future the Union’s economic and monetary policies should be designed while bearing in mind the possible repercussions on the domestic sphere.

Secondly, Italy has felt very alone when trying to cope with irregular immigration. Along with Greece, it is the country with the highest rate of irregular migrant arrivals on its shores but has received little of the solidarity it needed from the EU. As elsewhere in Europe, this has played right into the hands of the right-wing parties and will continue to do so if there are no improvements in the future.

Last but not least, a dwindling level of trust in institutions together with a growing disenchantment with politics explain a lot about the Italian voting preferences. The difference between the ‘old parties’ –FI and PD– and the ‘new parties’ is a symptom of this disenchantment –although admittedly the League (the extended version of Lega Nord) is not exactly a new political party, since it was established in 1991 and has been consistently repeating its extreme discourse since then–.

So… What next? The newly elected Parliament will meet for the first time on 23 March and choose the leaders of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Then the bargaining to create a new government will begin, but it will not be easy to design a winning coalition. In any case, the M5S will face a tough test: to become a strong partner in the government and shift its discourse from opposition rhetoric to policy making. If it fails, the right-wing bloc will set about seeking a partner. In any case, the political situation is likely to remain unsettled for some time longer.

Ilke Toygür

Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Associate Professor in University Carlos III of Madrid | @ilketoygur

Bibliography

Bhatti, Jabeen, Nikolia Apostolou, Eric J. Lyman & Evangeline O’Regan (2012), ‘Tax evaders in Greece, Spain and Italy better beware’, USA Today.

The Economist (2016), ‘The Italian job: Italy’s teetering banks will be Europe’s next crisis’.

Eurostat (2016), ‘General government gross debt – annual data’.

Henningsen, D.M. (2012), ‘The Origins of the Italian Sovereign Debt Crisis’, CMC Senior Theses Paper, nr 379.

ISTAT (2015), ‘Non observed economy in national accounts’, 4/XII/2015.

Nordsieck, W. (2016), ‘Parties and Elections Database’.

Poletti, Monica, Federico Vegetti & Paolo Segatti (2013), ‘When responsibility is blurred – Italian national elections in times of economic crisis, technocratic government, and ever-growing populism’, Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, vol. XLIII, nº 3, p. 329-352.

Verney, Susannah, & Anna Bosco (2013), ‘Living parallel lives: Italy and Greece in an age of austerity’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 18, nr 4, p. 397-426.

1 For more information see ISTAT Regional Accounts.