Theme

Argentina’s Stabilisation Plan has entered its decisive phase. The IMF must play a vital role.

Summary

This is the decisive moment to capitalise on the successes achieved so far by the Argentine Stabilisation Plan and the sacrifices asked of the population, to set the country on the path to eradicating the scourge of inflation, macroeconomic instability and recurrent crises.

The quickest, most reasonable and, indeed, most logical way to achieve this is a new agreement with the IMF to provide Argentina with fresh funds (international reserves that it currently lacks) to dispel the spectre of external debt restructuring, lift currency controls smoothly while keeping expectations anchored, and thus ensure the programme’s success.

Argentina has already travelled a long way on its own, without external conditions imposed by any outside agent, which, in the past, would have led swiftly to an IMF agreement: severe fiscal adjustment; a sharp tightening of monetary policy; a cleanup of the Central Bank’s balance sheet; a capital repatriation amnesty; and an ambitious agenda of structural reforms.

With these foundations, an agreement with the IMF is perfectly attainable. Achieving it would set a virtuous cycle in motion: the certainty of repaying foreign currency debt amortisations would further reduce country risk to levels compatible with Argentina’s re-entry into international capital markets; and lifting currency controls would enable the inflow of investments in strategic sectors that, under the RIGI framework, are waiting for the end of currency restrictions to be deployed.[1] All of this would likely result in a vigorous economic recovery.

One could argue that history is not on Argentina’s side: that the IMF’s exposure to Argentina is already too high; that it is its largest debtor; and that too many stabilisation plans have failed in the post-war period, even the most promising and enduring, like the Convertibility Plan of the early 90s. Also, that under these conditions, reaching a new agreement with the IMF will be difficult.

Perhaps so. But there are always moments in the lives of countries and institutions —and certainly of people— when, to make history, you must break with history. That is the challenge. Nothing more, nothing less.

Analysis

The Stabilisation Plan of President Javier Milei’s government, launched just days after he took office on 10 December 2023, has now entered its decisive phase.

The fiscal adjustment, the cornerstone of the plan, was much faster and more severe than one might have expected from a government with a minority in Congress, facing predictable resistance from unions and social movements. Yet, against all odds, this is exactly what happened, and the results have been remarkable. Although achieving these results has come at a high social cost (recession, declining incomes and rising poverty), approval ratings of the government are still very high.

How did we get here? Why are we now at a decisive phase? What role does the IMF play at this stage?

This analysis aims to answer these questions.

1. The pillars of the Stabilisation Plan

These are the essential components of the Stabilisation Plan: (1) a severe fiscal adjustment; (2) a severe monetary tightening; (3) a clean-up of the Central Bank’s (BCRA) balance sheet; (4) an end to monetary financing of the NFPS fiscal deficit and the BCRA’s quasi-fiscal deficit; (5) an initial devaluation of 100% in the official exchange rate and pre-announced 2% monthly depreciation, while retaining exchange controls; and (6) a capital amnesty.

1.1. Severe fiscal adjustment

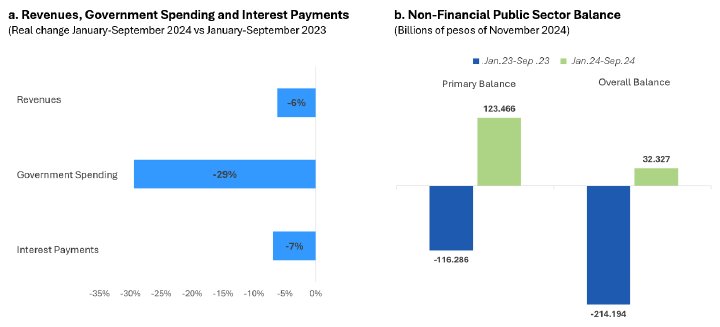

The fiscal adjustment amounted to around 5% of GDP, leading to a swift elimination of the fiscal deficit. It primarily focused on reducing primary public spending, with all spending categories experiencing significant real reductions compared with the first nine months of the previous year. The reductions included capital spending (-80%), transfers to provinces (-70%), public sector wages (-26%) and pensions (-23%) (see Figure 1 a-d).

Figure 1. Fiscal policy

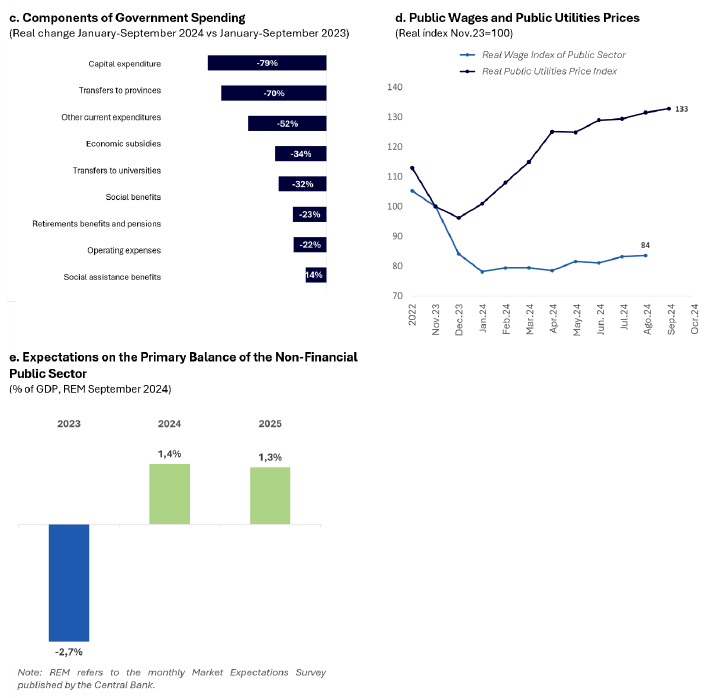

Figure 2. Monetary and exchange rate policy

1.2. Severe monetary tightening

The plan also began with a severe monetary tightening. Real liquidity in domestic currency dropped 20% to 30%, depending on the liquidity indicator used (see Figure 2.a). The resulting illiquidity is evident in the dramatic increase in the spread between the interest rate charged by banks on personal loans and the BCRA’s interest rate (previously on interest-bearing liabilities, now on LeFI).[2] The spread, which reflects the opportunity cost of holding liquid money, rose from an average of 2 percentage points (200 basis points) in November 2023 to an average of 25 percentage points (2500 basis points) between December 2023 and October 2024 (see Figure 2.b).

1.3. Clean-up of the Central Bank’s (BCRA) balance sheet

The BCRA’s interest bearing liabilities were exchanged for Treasury Notes (LECAP and LeFI), transferring the responsibility for interest and principal payments to the National Treasury (see Figure 2.c). This measure eliminated an automatic source of monetary expansion (the interest payments on BCRA liabilities) and restored the BCRA’s independence in setting the monetary policy rate.[3]

Additionally, puts held by the financial system were repurchased from banks, allowing the BCRA to extinguish almost 80% of this stock (see Figure 2.d),[4] thereby deactivating a potential source of monetary expansion outside of its control.

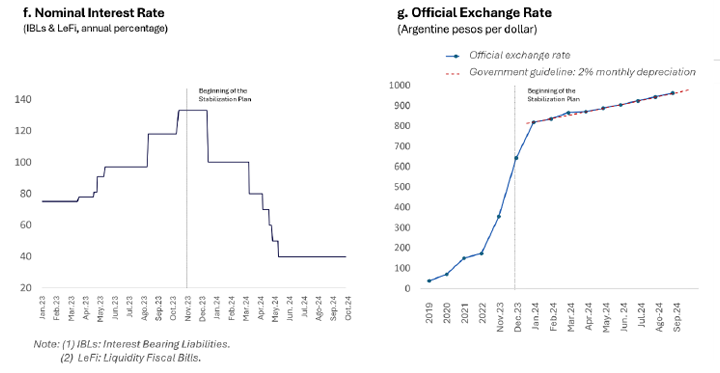

1.4. End of monetary financing of the NFPS fiscal deficit and the BCRA’s quasi-fiscal deficit

The combination of restrictive fiscal and monetary policies meant that in the first nine months of the year the main source of growth in the BCRA’s monetary base was the purchase of dollars to strengthen the international reserves position (see Figure 2.e). This was possible because the severe contraction in local currency liquidity not only led the markets to sell dollars to the BCRA for pesos, but also enabled the BCRA to issue its interest-bearing liabilities in domestic currency (now scarce and revalued) at substantially lower rates. This facilitated a dramatic reduction in the interest rate on the BCRA’s interest-bearing liabilities (see Figure 2.f).

1.5. Initial devaluation of 100% of the official exchange rate and pre-announced 2% monthly depreciation, while retaining exchange controls

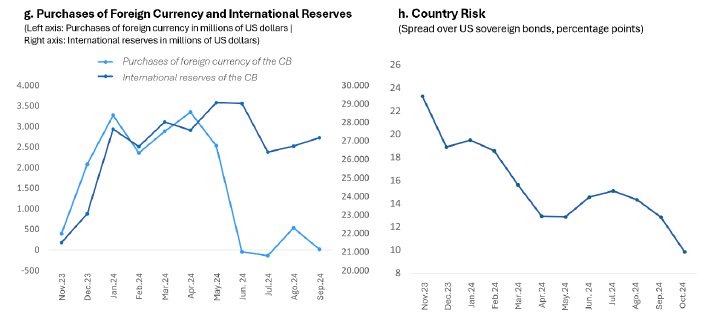

The official exchange rate acts as the monetary anchor of the plan. The maintenance of exchange controls, known as the cepo in Argentina, serves partially, and for practical purposes, as a substitute for the international reserves that the BCRA currently lacks to support the exchange rate parity (see Figure 2.g).

1.6. Capital amnesty

The capital repatriation amnesty introduced by the government is a scheme allowing individuals and companies to regularise undeclared assets, both in Argentina and abroad, by paying a special tax.[5] Furthermore, the government has announced its intention to eliminate the databases of those who participate in the amnesty, aiming to prevent these taxpayers from facing future taxes on the regularised assets.

To join the programme, taxpayers must open a Special Asset Regularisation Account (CERA) at an authorised local financial institution. The funds deposited in these accounts must remain in the system until 31 December 2025. If the regularised funds are invested in public securities issued by the Argentine government, taxpayers may be exempted from the special tax.

2. Macroeconomic outcomes

The macroeconomic results of the Plan came in fast:

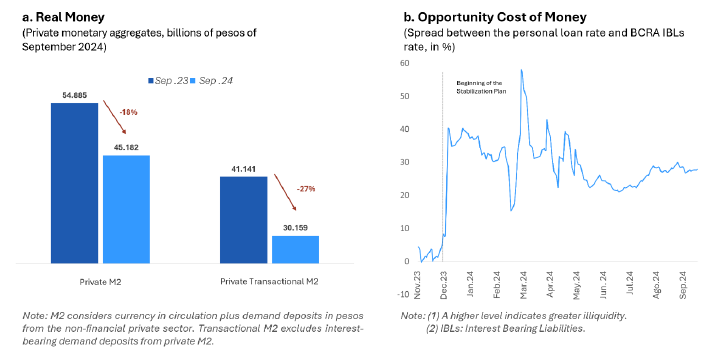

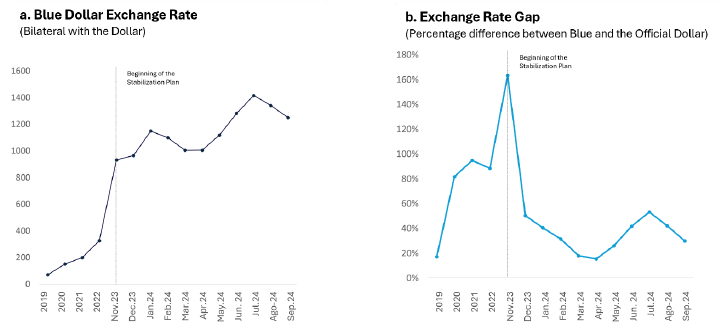

- The parallel or blue dollar stabilised, and the gap with the official rate narrowed from 160% at the start of the plan to less than 20% (see Figures 3.a and 3.b).

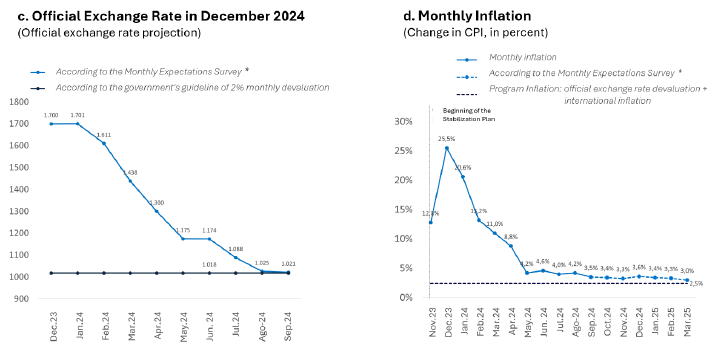

- Expectations for the official exchange rate aligned with the government’s announced guideline of a 2% monthly depreciation (see Figure 3.c).

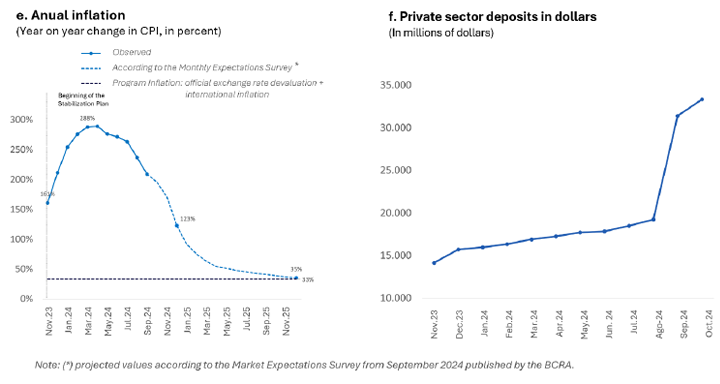

- Inflation decreased significantly, at a pace much faster than the market expected, and inflation expectations converged to the implicit guideline in the plan: an annualised devaluation of 27% plus international inflation (see Figures 3.d and 3.e).

- Primarily as a result of the capital repatriation amnesty, banking system deposits increased by over US$12 billion, reaching a higher level than at the end of former President Mauricio Macri’s term (see Figure 3.f).

- Due to peso illiquidity and, more recently, the capital repatriation amnesty, BCRA’s dollar purchases increased substantially, boosting international reserves (see Figure 3.g).

- Country risk dropped from 2,500 basis points at the start of the plan to less than 1,000, in recent weeks on the back of the success of the capital repatriation amnesty and its incentives to invest in government securities (see Figure 3.h).

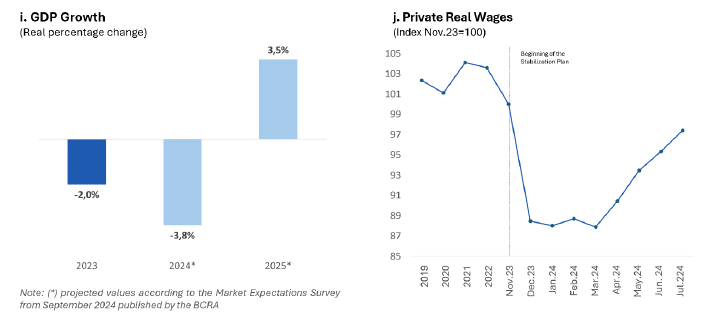

- After a sharp initial economic contraction project at 4% this year, a rebound is expected in 2025, with the economy projected to grow at 3.5%, following the typical pattern of stabilisation plans that begin with severe monetary tightening (see Figure 3.i).

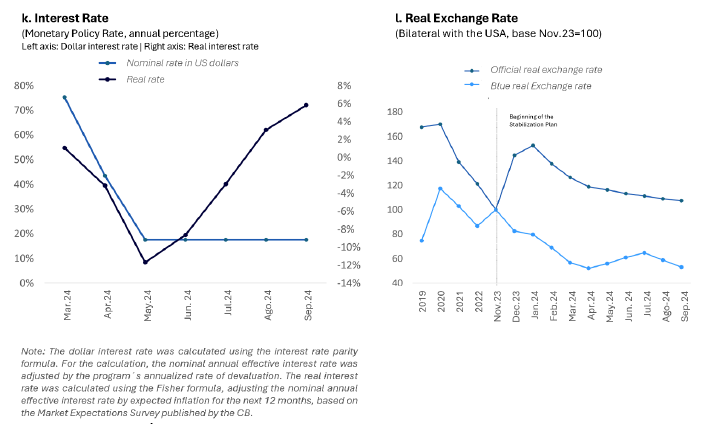

- Other real variables are also displaying common patterns observed in stabilisation plans of this nature: a sharp initial decline in real wages followed by a recovery (see Figure 3.j); initially negative real interest rates that later shift to positive levels (see Figure 3.k); and an appreciation of the real exchange rate (see Figure 3.l).

Figure 3. Macroeconomic outcomes

3. A decisive phase and the IMF’s vital role

The Stabilisation Plan has entered its decisive phase. To capitalise on the excellent results achieved so far and the significant sacrifices made by the population, the government needs to make a final push.

The next phase of the Stabilisation programme presents two major challenges: (a) lifting currency controls; and (b) meeting the foreign currency debt amortisation schedule in what remains of 2024 and 2025.

To address both challenges, Argentina requires a level of international reserves it currently lacks. To tackle the second challenge, the government is negotiating with a consortium of international banks to secure a short-term loan known as a ‘repo’ (repurchase agreement). Such an agreement would provide immediate funds by offering sovereign bonds or gold reserves as collateral, with a commitment to repurchase them at a later date. The primary goal of this repo is to strengthen the Central Bank’s international reserves and ensure debt payments due in January 2025.

However, to achieve the first challenge —lifting exchange controls smoothly—the funds from the repo are insufficient, thus delaying the timing for doing so.

Without access to the international capital markets, there is only one reasonable and logical way to simultaneously meet both objectives: a new agreement with the IMF that injects sufficient fresh funds to replenish Argentina’s international reserves.

If successful, this would set in motion a virtuous cycle: the assurance of foreign currency debt repayment would further reduce country risk to levels compatible with the re-entry of Argentina to the international capital markets; and lifting currency controls would open the door for investments in strategic sectors that, under the RIGI framework, are waiting for currency restrictions to be lifted. All of this would likely result in a vigorous economic recovery.

How much fresh funding are we talking about? Considering the remaining external debt amortisations for 2024 and 2025 (excluding those with the IMF, multilateral organisations and official bilateral agreements) and the reserve stock needed to lift currency controls without triggering the risk of destabilising expectations and ‘de-anchoring’ the Plan, we estimate that Argentina requires around US$45-48 billion in gross international reserves. Currently, it holds US$28 billion.

Is an agreement of this magnitude possible? Let us take a closer look.

4. Towards an agreement with the IMF

The key elements in negotiating an agreement with the IMF typically involve the following:

- A fiscal target.

- A reserve accumulation target.

- The definition of the exchange rate and monetary policy regime.

- The amount of new financing that would be provided by the IMF.

Agreeing on a fiscal target should not be an obstacle in the negotiations. Argentina has already implemented a fiscal adjustment of 5% of GDP by its own decision, without any external conditions imposed. It currently has a primary surplus of 1.4% of GDP, and markets expect that surplus to continue into 2025. This ensures that Argentina will maintain balanced fiscal accounts this year and the next.

The internation reserves target should aim to increase the stock of international reserves from US$28 billion to US$45-48 billion over the next three years, implying an annual reserve accumulation target of US$5-7 billion per year, a goal that is achievable solely through seigniorage and the inflation tax.

With the ‘cleanup’ of the BCRA’s balance sheet already completed and monetary policy instruments restored, the exchange rate regime after lifting exchange controls must be defined. Two constraints limit this transition.

First, Argentina will need to accumulate international reserves for the foreseeable future by purchasing dollars in the market. This means the exchange rate cannot float freely downward, as the BCRA will have to intervene by buying dollars to meet the reserve accumulation target.

Secondly, the exchange rate cannot float freely upward either. In a highly dollarised economy like Argentina’s —where the dollar is both the unit of account and store of value— and with very low levels of monetisation in the domestic currency, the interest rate lacks the muscle as a monetary policy tool to stabilise expectations.

This leaves two options: a managed float (with reasonably predictable intervention criteria) or an exchange rate band. In the latter case, it will be necessary to define the band’s width and the monthly depreciation rate for its upper and lower limits.

This last point is primarily a technical matter, well within reach of an agreement, although it may require the usual arduous and heated discussions with IMF staff.

Finally, after resolving the first three negotiation points, the amount of new financing the IMF will provide under the new programme must be agreed upon. These funds are necessary to dispel the spectre of external debt restructuring and, more importantly, to allow the exchange-rate regime to anchor expectations and meet the international reserves accumulation target, and to ensure the programme’s success.

Conclusions

Argentina’s Stabilisation Plan has entered its decisive phase. This is the time to capitalise on the successes achieved so far and the sacrifices asked of the population, putting Argentina on the path to eradicating the scourge of inflation, macroeconomic instability and recurring crises.

The quickest, most reasonable and, indeed, most logical way to accomplish this is through a new agreement with the IMF, which would provide Argentina with fresh funds to dispel the spectre of external debt restructuring and, more importantly, to lift exchange controls smoothly, keeping expectations anchored and thereby ensuring the programme’s success.

Argentina has already travelled a long way on its own, without external conditions imposed by any outside entity, a path that, in the past, would have quickly led to an agreement with the IMF: a severe fiscal adjustment; sharp monetary tightening; a clean-up of the BCRA’s balance sheet; a capital repatriation amnesty; and an ambitious agenda of deregulation and structural reforms.

With these foundations, an agreement with the IMF is entirely within reach. Achieving it would set a virtuous cycle in motion: the assurance of foreign currency debt repayments would further reduce country risk to levels compatible with the re-entry of Argentina to the international capital markets; and lifting currency controls would pave the way for investments in strategic sectors which, under the RIGI framework, are waiting for currency restrictions to be lifted. All of this would likely result in a vigorous economic recovery.

One could argue that history is not on Argentina’s side, that the IMF’s exposure to Argentina is already too high, that it is its largest debtor and that too many Stabilisation Plans have failed in the post-war period, even the most promising and durable, like the Convertibility Plan of the early 90s. Under these conditions, reaching a new agreement with the IMF will be challenging.

Perhaps so. But there are always moments in the lives of countries and institutions —and certainly of people— when, to make history, one must break with history. That is the challenge. Nothing more, nothing less.

[1] The Incentive Regime for Large Investments (RIGI) is an initiative aimed at attracting significant national and foreign investments in key sectors of the Argentine economy: mining, gas and oil, renewable energy, agribusiness and technology. It offers a series of tax, customs and exchange-rate benefits to promote large-scale projects.

[2] LeFi stands for ‘monetary regulation bills’.

[3] The transfer of interest payments from the BCRA to the Treasury amounts to around 0.5% of GDP, requiring an additional fiscal effort to cover these expenditures without monetary financing.

[4] A put holder has the right (but not the obligation) to sell Treasury bills to the BCRA at a predetermined price and within a set period if their value falls below the price established in the put contract. To get a sense of scale, prior to the voluntary exchange operation, if all banks simultaneously exercised their rights (which they could do at any time within the period specified in the put contract), the BCRA would have had to issue the equivalent of an entire monetary base.

[5] This programme is structured in three stages with progressive tax rates:

- Stage 1: Until November 8, 2024, with a rate of 5% on amounts exceeding $100,000.

- Stage 2: From November 9, 2024, to February 7, 2025, with a rate of 10%.

- Stage 3: From February 8 to May 7, 2025, with a rate of 15%.

The first $100,000 regularised is exempt from this tax.