Theme

This paper contends that the construction of a cooperation agenda between the EU and South America must consider a set of exogenous and endogenous variables that encompass geopolitics, security concerns, global governance structures and mechanisms. However, it must also take into account the domestic challenges Latin American countries need to overcome to correct their democratic deficits and the negative social and political effects of their own economic development models.

Summary

During the first years of the 21st century progressive Latin American governments defended regional integration and promoted more autonomous foreign policies. Internally, they implemented social inclusion and poverty-reduction policies. Externally, the narrative of regional integration added a clear emphasis on South-South relations and the broadening of global and interregional political coalitions and partnerships. However, at the end of the second decade, the ‘pink’ tide seems to have reached its limits, and new avenues for regionalism, inter-regionalism and cooperation with the EU may be opening up – not without political controversy and trade-agricultural issues at stake. This paper presents a two-fold argument: the construction of a cooperation agenda between the EU and South America must consider a set of exogenous variables (geopolitics, security and global governance); however, it must also consider domestic politics and the political economy of regional integration in Latin American countries.

Analysis

Introduction

The first years of the 21st century witnessed a turnaround in Latin American regional politics. In several important countries, especially Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Paraguay, Venezuela and Uruguay, progressive governments took on the political banner of regional integration and promoted more autonomous international strategies vis-à-vis the US and the Western countries. Internally, although with variations, these governments fostered social inclusion and recognition policies that achieved results that have been recognised world-wide in the fight against poverty, inequality and discrimination. At the external level, the narrative of regional integration has added a clear emphasis on South-South relations and the broadening of global and interregional political coalitions and economic partnerships, including the IBSA Forum (India, Brazil and South Africa), the BRICS grouping and its enlarged summits (with African countries in Durban in 2013 and South-American nations in Fortaleza in 2014), South American-African (ASA) and South American-Arab nations (ASPA) summit meetings, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, amongst others.

At the outset of the second decade, however, a series of political events contributed to mitigate the importance of democratic progress and the achievements of social policies in the region. The summary dismissal of Fernando Lugo in June 2012, through a political trial conducted and voted by the Paraguayan Congress in less than 48 hours, revived debates about the processes of institutionalising democracy in Latin America, but also about the role that regional organisations (such as MERCOSUR and UNASUR) might play in guaranteeing democratic order without the interference of external powers. On the one hand, some analysts have pointed out that the entire process was approved by a large majority of deputies and senators, as the Paraguayan Constitution foresees, and therefore that it was an orderly, peaceful and respectful trial in terms of legality and existing political institutions. On the other hand, many have denounced a new version of a white coup with the support of the conservative mass media, the parliament and sectors within the judiciary. The Paraguayan case could be included in a series of coup attempts in South America (such as Jamil Mahuad’s in Ecuador in 2000, Hugo Chávez’ in 2002 and Rafael Correa’s in Ecuador in 2010), the Caribbean (Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s in Haiti in 2004) and Central America (Manuel Zelaya’s in Honduras in 2009). The latest case was Brazil’s 2016 controversial impeachment of President Rousseff. In an article published in the Argentine newspaper La Nación on 24 June 2012, Juan Gabriel Tokatlián called the phenomenon neogolpismo: formally less virulent coups, led by civilians with support or the complicity of the military and preserving a certain institutional appearance (Milani, 2012 & 2017).

Given the context, this paper argues that the construction of a cooperation agenda between the EU and South America must consider not only a set of exogenous and endogenous variables that encompass geopolitics, security concerns, and global governance structures and mechanisms, but also the domestic challenges in Latin America countries that would be necessary to overcome both democratic deficits and the negative social and political effects of their own economic development models. The following two sections focus on each of these dimensions.

Systemic and regional dimensions: the heterogeneity of regional integration processes

The heterogeneity of regional integration and cooperation processes in Latin America since the 1990s is a challenge to the future cooperation agendas between the region and the EU within a new international order currently rooted in economic nationalism and political populism in different geographical contexts. In the dominant narratives in Latin America in the post-Second World War, regional integration was represented as a strategy to cope with the economic and political dominance of the US across the Americas. Regional integration aimed to create alternative scenarios for international relations within the region, thus reducing its excessive dependence on Washington, but also to increase the region’s bargaining power (or the bargaining power of particular countries) in negotiations with the US. Although such an expectation was not homogeneous, regional integration was part of ECLAC’s set of economic policy prescriptions in the 1940s and 1950s. Along with the need to change the development model from exporting raw materials and agricultural commodities towards an industrial economy, ECLAC championed the adoption of the import substitution strategy and advocated regional integration policies.

Over a long period of its history, Brazil was not very enthusiastic about regional integration. Its economic model (based on exports to Europe and the US) and the language factor (being the region’s only Portuguese-speaking country) contributed to its lack of enthusiasm. It all began to change as a Latin American school of thought based on the theory of dependency, and on a new understanding of centre-periphery relations, grew in intellectual and political importance. There was an intense exchange of ideas between Brazilian scholars and their peers in the region and in other countries, and together they created a rich and truly original theoretical framework built from the developing world’s point of view. Grounded in an analysis of the ‘deterioration in the terms of trade’ phenomenon, they argued that countries exporting industrialised goods add more value to their trade than those selling primary products. Furthermore, the difference tends to deepen over time, leading the proponents of this approach to denounce the failures of traditional economic thought, which focuses on the comparative advantages of nations.

Paradoxically, ECLAC and the dependencia theory did not take into account that the import substitution model would discourage the export efforts of Latin American countries and the creation of a common Latin American economic space given the strong inducement to national industrial and commercial protection. This paradox can be considered one of the factors responsible for the relative failure of the various attempts to implement regional integration projects in the 1960s and 1970s. Another restriction stemmed from the relative structural asymmetry between Latin American countries, on the one hand, and the regional economic giants (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico), on the other. Political differences between them might also have weighed on this unwillingness to engage in regional cooperation: democratic transitions boosted interstate cooperation on both economic and non-economic issues (Lima & Milani, 2016).

This suggests three elements to be considered in order to understand the relationships between the development model, the political regime and regional integration processes, and also why these relationships matter for a future cooperation agenda between the EU and South America. The first is the effect of the political and economic contexts on the relationships between the variables. Argentina and Brazil experienced long periods of authoritarian rule, but this political coincidence did not generate cooperation between them. On the contrary, as the bilateral conflict over Itaipu in the 1970s shows, both military regimes extended their historical rivalry for the control of the River Plate area (Lima, 1990). It was only with the return to democracy in the 1980s that it was possible to overcome these historical divergences and initiate a process of cooperation between the two countries that would later lead to the creation of MERCOSUR in 1991. The second aspect to be considered is Washington’s role: during the Cold War, US action was a crucial parameter in determining the degree of freedom of Latin American countries in implementing their models of development and regional cooperation. Third, there are path-dependency effects of integration processes that imply costs embedded in any potential future changes by political decision: at the end of the Cold War, Mexico’s option for NAFTA and Brazil’s for MERCOSUR conditioned any subsequent moves by both countries in their respective choices of regional models and international trade integration.

In general, Latin America’s regional integration initiatives have been neither linear nor convergent with US-proposed regional cooperation initiatives. To understand this, it is necessary to distinguish conceptually the integration processes from those of regional cooperation. In the post-Second World War, the regional integration model that oriented Latin American countries was the European project, aiming at eliminating restrictions on the free exchange of goods, services, capital and people and, in its last stage, reaching the delegation of sovereignty to some new forms of political authority. Latin American countries wanted to emulate the European project of an integrated economic space and a regional coordination of public policies. Regional cooperation, on the other hand, involves cooperation processes in different areas (military, political, economic, energy and technical), thus reflecting foreign policy and geostrategic priorities. Regionalism, unlike integration processes, has much less ambitious objectives and as it is a predominantly intergovernmental dynamic involves varying degrees of coordination of government policies and virtually no delegation of sovereignty, except for the specific coordination of the issues being negotiated.

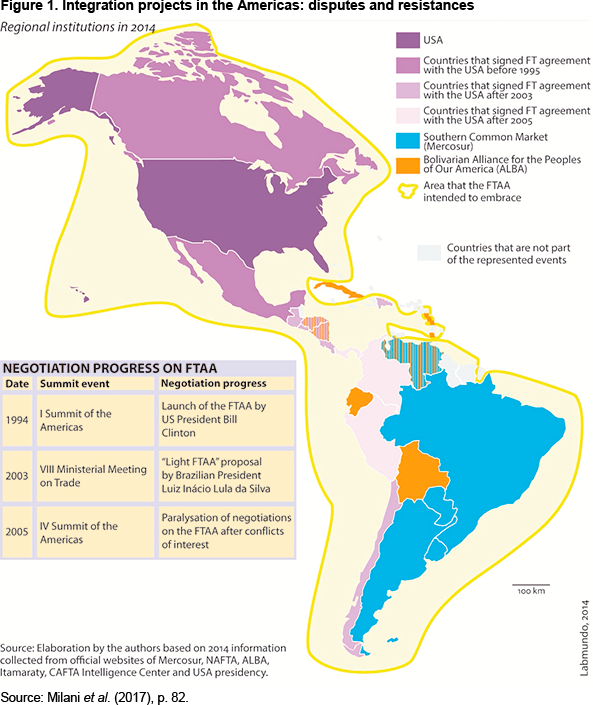

With the end of the Cold War, the processes of integration and regionalisation converged under the leadership of the US and neoliberal governments in Latin America. The first step was taken by the US in agreeing to a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Canada, changing its previous strategy of stressing multilateral liberalisation alone, followed by its expansion with the creation of NAFTA, including Mexico. This regionalism, under US leadership, will be guided by the logic of economic openness and trade liberalisation. The regional cooperation model was profoundly revised once the neoliberal consensus in politics and economics began to break up in the early 2000s with the election of left-wing and centre-left governments in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela. South America thus saw a significant change in its political and ideological orientation, which were also diverse in relation to each other but with similar orientations regarding the overthrow of neoliberal dogma, the return of state economic coordination and an adjusted developmental vision of the constraints of globalised capitalism, the priority accorded to the need for social inclusion and a revisionist foreign policy, but also with variations between countries with a progressive orientation. Figure 1 illustrates the complexity and heterogeneity of regional integration and cooperation in Latin America, the Caribbean, and North and South America.

In Brazil, a properly South-American outlook is a recent phenomenon that began in the 1980s; it was further pursued in the 1990s and more decisively bolstered during the Lula government (2003-10). South America came to be seen as an area with greater legitimacy for a regional leadership project. In addition, it was felt that Latin America had lost its legitimacy as a region, after Mexico’s decision to join NAFTA in 1994. In this context, Brazilian diplomacy worked to retrieve the concept of South America during Ambassador Celso Amorim’s first term as Chancellor (under President Itamar Franco), initially by proposing a free-trade area in the region. This diplomatic priority was weakened during the Cardoso government, despite organising the first ever meetings of South American heads of state in 2000 and 2002.

The political focus on South America coincided with a reactive US withdrawal from the region due to its new strategic priorities after 9/11 (the Middle East and Central Asia) and the geopolitical and geo-economic stress on the Asia-Pacific region, due either to the shift of the dynamic axis of capitalism in that direction or as a strategy to contain China’s global emergence. The new regional and global context is much less restrictive than that of the 1990s and the countries of South America will enjoy a greater degree of freedom to deepen or even promote significant changes in their respective models of development and international economic insertion. In the 2000s the homogenising scenarios of the previous decade in economic policy and state vision were revised and the narrative that came to be imposed was the de-concentration of global power and the transfer of the dynamic axis from West to East. It moved from a narrative marked by unipolarity and the victory of liberal democracy and markets to the vision of economic multipolarity and the plurality of modes of organising relations between the State and the market. This description, however, is prey to much simplification, reflecting the underlying ideological component. It is important to highlight a differentiating element with respect to the 1990s: the diversity and heterogeneity of national experiences in the fields of politics and economics. Although capitalism and democracy are the dominant processes, the variations of their different modalities in the political and economic sphere are considerable. South America is one of the regions that exemplifies this diversity even today, despite the crises that mainly penalised the models in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela (Milani et al., 2016).

The new political configuration is expressed in the non-convergence between the various processes of economic integration and trade regimes, such as: NAFTA, encompassing North America and Mexico; the Pacific Alliance with the participation of Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Peru; MERCOSUR, including Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela; Chile, Colombia and Peru with a clear preference for Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with the US and countries outside the region; and ALBA, under the leadership of Venezuela, Central American countries and Cuba. Another dimension that distinguishes this moment from the first years of the 21st century is the emergence of sub-regional initiatives involving various areas of cooperation. In a certain sense, the diversity and heterogeneity of trade regimes, which derive from the differentiation between Latin American countries in terms of their productive patterns, models of democracy and foreign policy options, seem to stimulate subregional cooperation initiatives. This is the moment when the dynamics of integration models are removed from the processes of regionalisation, which emphasise the subregional dimension.

In this new configuration, the main regionalisation initiative was the creation of UNASUR in 2008, incorporating all 12 countries of South America and that arose not as an alternative to existing trade regimes but as a way of going beyond mere trade integration, allowing other forms of regional cooperation and, more importantly, overcoming the constraints generated by the existence of their respective trade regimes in the region. The institutional design of UNASUR allowed the creation of councils whose purpose is to assist and propose public policies for the bloc from their respective areas. The Council of Defence of South America and the Health Council were followed by the Councils against Drug Trafficking, Infrastructure and Planning, Social Development, Education, Culture, Science, Technology and Innovation. In addition to establishing an institutional framework for expanding cooperation in a reasonable number of regional public policies, the councils have led to the creation of domestic constituencies in the respective participating countries involving political and economic actors that are also diverse, thus creating within their respective civil societies actors committed to regionalisation in multiple facets. Among them is the South American Council on Infrastructure and Planning (COSIPLAN), created to replace the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA), proposed by the Cardoso government in 2000 (Lima & Milani, 2016).

Domestic challenges in Latin American countries

The creation of UNASUR in 2008, changes in MERCOSUR with a greater emphasis on democracy-building and human rights, the creation of civil society participation mechanisms and an unprecedented concern with structural asymmetry and the establishment of structural funds under FOCEM, the constitution of ALBA under Venezuela’s leadership and the 2010 foundation of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean nations (CELAC), among other factors, have led to a model of regionalism rooted in the primacy of the political agenda, the role of the State in economic coordination and a deeper concern with social inclusion policies. In some cases, such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador (under Rafael Correa), a markedly anti-liberal dimension has been added to their respective constitutional frameworks, and their foreign policies deny the dynamics of open regionalism advocated by the US.

The creation of the Pacific Alliance, with the addition of Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Peru, added further diversity to the regional space. In line with the Free Trade Agreements and formalising the ties that these countries already had with the US on the open regionalism model, the Alliance has a clear geopolitical dimension. In terms of political-ideological debate, it has become common currency to present the idea of competition between two different models of regionalisation, which helps to understand the priority given by Brazil to Venezuela’s admission to Mercosur. Naturally, the Pacific Alliance constitution gives a greater weight to the group of countries that focus on market solutions, trade liberalisation and integration into global production chains, with foreign policies that converge to a greater extent with the US and are favourable to the status quo of global governance.

It is too early to assess whether we are actually facing two alternative models of regionalism since the most pessimistic predictions regarding the consequences of China’s slow-down and falling commodity prices in South America, as well as regarding political scenarios in the region, in particular with the increase in political uncertainty after Hugo Chávez’s death and the current crisis in Venezuela, but also in Brazil. Some countries may have incentives to adhere to new transcontinental initiatives, trade liberalisation and investment arrangements. In any case, we seem to be at the start of a new process of integration and regionalisation in the region due to the changes in the South American political scene with the deep crisis in Venezuela, the political and economic crisis in Brazil that has practically paralysed regional policy initiatives and the results of the presidential elections in Argentina following Macri’s victory. In Latin America as a whole it is worrying to recall that national levels of support for democracy are at around 54% (Malamud, 2017, p. 30).

Will domestic changes influence the foreign policies and regional integration of Latin American countries? Will countries such as Brazil (as the main economy in Mercosur) and Mexico (in the Pacific Alliance) converge in their regional trajectories and foreign policy agendas? At a recent ministerial meeting in Buenos Aires in April 2018, Ministers from Mercosur and the Pacific Alliance signed a declaration that called for trade facilitation measures, the simplification and convergence of customs rules, the harmonisation of rules of origin and support for small and medium-sized businesses. Such a political move would have been unthinkable when the Workers’ Party led the governmental coalition in Brazil. That is, governments do matter in foreign-policy making, and in Latin American liberal democracies with strong presidential systems elections can also prompt significant changes. In 2018 both countries have presidential elections, Mexico in July and Brazil in October.

Aside from electoral results, it is also important to take into account structural and systemic variables, such as the political economy of the two regional integration models and the economic convergence indicators within and across the two blocs. As Ricardo Carneiro recalls, despite the expansion of trade agreements in the 1990s and during the first decade of the 21st century, Latin American regional integration remained stable compared to other regions. On average, less than 20% of the exports from Latin American and Caribbean countries have a regional destination. The figures are smaller in the case of Mercosur (15%) and derisory as regards the Pacific Alliance (4%). The result is mainly due to the characteristics of the productive structures of both North and South America. In the former case, industrial activity is concentrated in assembly (maquilas) and favours linkages with supply centres and consumer markets (mainly the US). In the latter case, the relatively lower weight of industry in relation to commodity production encourages outward linkages, in particular with China, to the detriment of intraregional trade flows, whose growth would depend to a large extent on the deepening of value chains (Carneiro, 2007). In general, South America as a whole depends on commodity exports to finance intra-regional imports, while Brazil is the only country that has recently increased its intra-regional exports of manufactured goods (Bastos, 2012). Considering these trends in political economy, what impact will changes in government have on regional integration models and their respective relations with the EU in the near future?

Conclusions

In June 2015 the latest EU-CELAC Summit was held in Brussels and an Action Plan was defined in 10 priority areas for bi-regional cooperation: (1) science, research, innovation and technology; (2) sustainable development and the environment, climate change, biodiversity and energy; (3) regional integration and interconnectivity to promote social integration and cohesion; (4) migration; (5) education and employment to promote social integration and cohesion; (6) the world drug problem; (7) gender issues; (8) investment and entrepreneurship with a view to sustainable development; (9) higher education; and (10) citizen security. It was expected that the next EU-CELAC Summit would be held in El Salvador in October 2017, which was presented as a great opportunity to take an important step forward in the consolidation of Euro-Latin-American relations. However, at Latin America’s request, due to the Venezuelan crisis, the Summit was postponed (Malamud, 2017, p. 77).

European regionalism differs greatly in its institutional form from other experiences in North America, Latin American, Africa, and Asia. Values related to liberal democracy define the EU’s membership rules and governance in the EU is driven by functional needs, thus having a large bureaucratic component. EU governance occurs at subnational, national and European levels, and its processes lead neither to unification through the creation of a European supranational political community nor to its fragmentation into national or subnational politics. It is true that the European polity suffers from persistent decisional inefficiencies from such an in-between status; despite that, it has been mirrored as a political model by many Latin American leaders, placing development in the region between an open economic perspective and demands for employment and inclusive social policies (Katzenstein, 2005; Santander, 2013).

As Sujatha Fernandes (2008) affirms, it is not clear if the EU is still an inspiration for Latin American leaders but neither is it clear if the US under Trump will exercise any influence in the region. Sebastian Santander (2013) reminds us that the EU is now seeking to bind ‘rising’ powers through ‘strategic’ partnerships. Yet it has long favoured relations with regional blocs rather than individual relations with countries, as in its relations with Latin America. The EU has especially focused on its relations with Mercosur, but it has recently established a direct and regular channel with Brazil through the so-called ‘strategic’ partnership. What are the reasons for this new kind of partnership? What interests are at stake? It would seem that the EU’s strategic partnership with Brazil is not only aimed at capturing new markets for European business but also at increasing the EU’s visibility and recognition as an international actor and demonstrating its ability to play in a state-centric world. However, in doing so, is the EU reversing its strategic logic? Is it moving from a strategy based on the idea of being a normative actor that promotes international regionalism and interregional relations to a Realpolitik approach that enhances the power of ‘rising’ states? In other words, what will the EU give priority to: the region (Latin America), the regional integration actor (MERCOSUR) or the country (Brazil)?

Carlos R.S. Milani

Associate Professor at the Rio de Janeiro State University’s Institute for Social and Political Studies (IESP-UERJ) and Research Fellow at the Brazilian National Science Council (CNPq)*

References

Bastos, Pedro P.Z. (2012), ‘The political economy of South American integration after the world economic crisis’, in Stefan Bojnec, Josef C. Brada & Masaaki Kuboniwa (Eds.), Overcoming the Crisis: Economic and Financial Developments in Asia and Europe, University of Primorska Press, Koper, p. 283-332.

Carneiro, Ricardo (2007), ‘Globalização e integração periférica’, Texto para Discussão, nr 126, Instituto de Economia, UNICAMP.

Fernandes, Sujatha (2008), ‘Latin America looks towards European Union’, Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 43, nr 32, 9/VIII/2008, p. 12-13.

Katzenstein, Peter J. (2005), A World of Regions, Asia and Europe in the American Imperium, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Lima, Maria Regina Soares de (1990), ‘A Economia Política da Política Externa Brasileira: Uma Proposta de Análise’ Contexto Internacional, vol. 6, nr 12, p. 7-28.

Lima, Maria Regina Soares de & Carlos R. S. Milani (2016), ‘Política externa, geopolítica e modelos de desenvolvimento’, in Maria Regina Soares de Lima, Carlos R.S. Milani & Enara Echart Muñoz (Eds.), Cooperación Sur-Sur, política exterior y modelos de desarrollo en América Latina, CLACSO, Buenos Aires, p. 21-40.

Malamud, Carlos (2017), ‘¿Por qué importa América Latina?’, Informe Elcano, nr 22, Elcano Royal Institute, December.

Milani, Carlos R.S. (2012), ‘Crise política no Paraguai: um teste para a região?’ Carta Capital, 6/VI/2012.

Milani, Carlos R.S. (2017), ‘Brazil, democracy at stake’, Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, University of California at Berkeley, Spring, p. 52-59.

Milani, Carlos R.S., Enara Echart Muñoz, Rubens de S. Duarte & Magno Klein (2016), Atlas of Brazilian Foreign Policy, CLACSO/EdUerj, Buenos Aires & Rio de Janeiro.

Sebastian Santander (2013), ‘L’Union européenne, l’interrégionalisme et les puissances émergentes. Le cas du partenariat euro-brésilien’, Politique européenne, vol. 1, nr 39, p. 106-135.

* Between January and December 2017, the author was Visiting Researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. His research agenda includes Brazilian foreign policy, comparative foreign policy and development cooperation policies and politics. His latest books are Brazilian Cooperation Agency: 30 years of History and Futures Challenges (2017), Atlas of Brazilian Defense Policy (2017) and Atlas of Brazilian Foreign Policy (2016).